$100,000 for Three Pages of Writing (For Real)

The Novelry Prize and How to Write a Great Three Page Opening

“Biggest” News in Books: The $100,000 Novelry Prize

It reads like a typo or an April Fool’s joke, but alas it is not. The Novelry, a UK-based organization that deals with the earlier stages of writing before the publishing process, but with an eye to get people into the publishing pipeline, it seems — is offering a $100,000 dollar prize in a contest that judges the best three page opening of a novel. That’s right, 6.5x the prize money awarded to Pulitzer winners for a word count of 1,500 (they must not double space). It must be noted for any hopeful writers out there that this comes with an entry fee of $15 bucks per submission—which means they need about 7,000 people to enter to cover their prize, not unimaginable.

But this begs the question: What can you tell about a novel from its first three pages? I wrote about “early warning signs” a couple of weeks ago, where I said you could usually tell 60-80% of your personal (not professional) feelings by about 60 pages into manuscript. So, what can you tell through three? I’d argue it’s not a great way to judge a novel at all. Especially if you believe, as I do, that a novel becomes a living, breathing thing, somewhat out of a writer’s control by the time it’s finished. That it is less about individual sentences and more the complete whole, their connectivity. There are plenty of very good and even great novels that don’t have one sentence you would print out and hang up on your wall, but strung together they make something magnificent.

I’ve also said elsewhere that the most common “shape” of a novel that isn’t working is “the spool”— a novel that starts off strong and becomes thinner and thinner as it goes. Writers, understandably, probably pour the most time into the start of the novel. The first couple of pages are the setup and also what readers will read first…duh…to decide if they want to continue.

Flaws of judging a novel on three pages aside, with this $100,000 headline, it’s a thought exercise almost too intriguing to ignore. It’s an opportunity to interrogate the common wisdom of what makes a good opening and perhaps give some advice to any aspiring writers who wish to take their shot at winning Novelry’s ten dimes. But instead of covering the classic openings — Leo Tolstoy, Shirley Jackson, Herman Melville — or re-citing the contemporary novels with killer openings, we’re going to replicate the Novelry’s mission here and dive into recently published contemporary fiction. Favoring the very recently published — somewhat arbitrarily — I’ve taken the top 100 hardcover fiction titles published this April (ranked by sales) and read the first three pages of each (How many hardcover sales makes you a top 100 hardcover fiction book published in April? About 100 copies). First, let’s talk about some critical observations that emerged from reading so many openings back-to-back, and then we’ll explore how the best three of the bunch subvert what doesn’t work about some of these not so good openings and what is effective about them.

*Wait, How Long Did This Take? *

Not as long as you’d think. The math of reading three pages of one hundred books does not add up to the time it takes to read a 300-page book. It was a bit surprising how much less mentally taxing a three-page rule was, actually. It only took an hour or two.

What Doesn’t Work

Info Dumping

A good portion of the fiction published in April of 2025 detailed the exact age of their protagonist in the opening three pages. There’s nothing wrong with this per se, but it was indicative of an issue that could be categorized as “hard facts my reader needs to know.” A sort of A/S/L protocol for fiction. It’s common advice to establish high stakes in the first pages (i.e. “put a dead body on the first page”) and the kind of cultural truism that the Novelry prize is feeding off. But I found the rush to make the stakes urgent and clear often having the opposite of the intended effect. So, in a hurry not to lose the reader, writers are often including the most essential information and assuming that their audience will care without focusing on more interesting ideas or phrasing that gives them reasons to.

Genre Assumptions

A lot of the more commercial works of genre, running the gambit from romance, to science fiction, to thriller, to fantasy, announced themselves fairly loudly in the first three pages. As in: “It was day five on planet Zornob, and their coffers of Lilith coin were running dangerously low after the trading war in the greater galaxy heightened.” Or in romance, something like: “Jane was fifty, she had been to over three hundred weddings in her life, she’d counted the invitations stored in a plastic bag in the deepest reaches of her closet. Her friends weren’t getting married very often anymore so this was very likely last wedding to find the true love of her life.” Maybe even those made-up sentences have too much mystery to them. The point is that the subpar openings tended to rely on some kind of pre-knowledge the reader has to the type of story being told (this should be contradictory to info dumping but somehow isn’t). Readers who read a lot in the same genre probably don’t mind as much, but I bet even they would be more engaged if writers were a bit more patient and didn't rush to pack the tropes in within the first three pages.

Voice Over

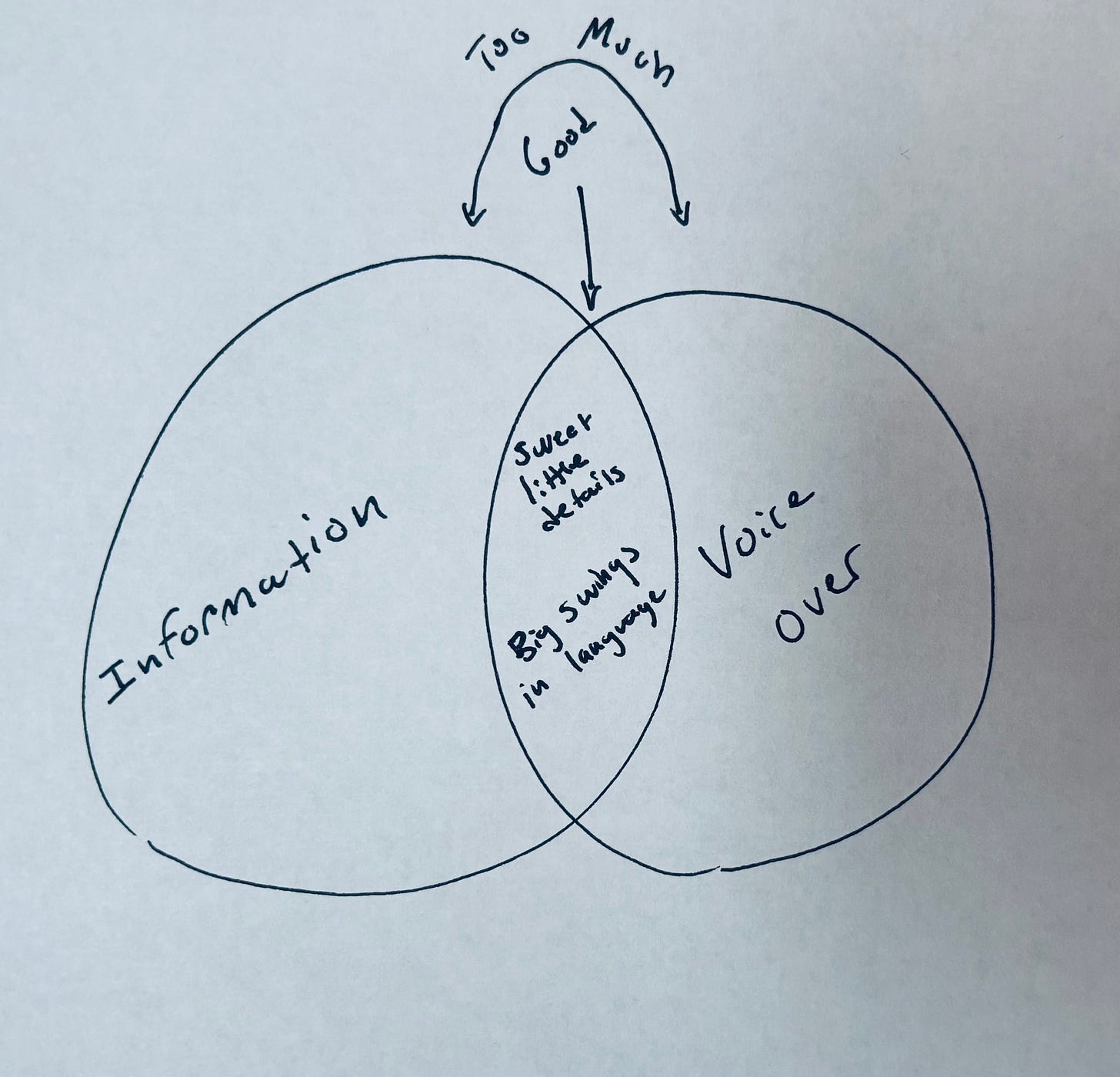

Whereas assumptions might be the genre writer’s Achilles Heel, more literary openings I often saw relying on a sort of voice over technique, where the character tries to tell you who they are to lay out the tonality and stakes of the novel in the introduction. They’ll say something like: “I’m a liar and a thief. A rogue and reprobate. The kind of person who keeps every promise but have only made three in my life.” Chuck Palahniuk, maybe borrowing from someone else, calls this “Big Voice” in his great how-to-write memoir Consider This. This type of writing can be engaging, but gets tiresome fairly quickly if not backed up by some concrete details and storytelling. It’s the opposite side of the spectrum from commercial writers who dump information but sometimes lack big swings — the best is obviously a happy marriage of both, big swings in language and ideas with lots of sweet little details.

Interlude: Bestselling Authors Know What They’re Doing

It’s easy for literary people to malign commercial bestsellers, especially when you only read a big bestseller every once in a while. But through the exercise of reading dozens and dozens of samples you do really gain an appreciation for the notch bestselling authors often are above other similarly commercially-written books. The three top selling new books published last month by Emily Henry, Jeneva Rose, David Baldacci, and Nita Prose, all have a way above average opening three pages. I’m not including them as examples, but they are worth checking out for how some of the elements described above which, in less experienced writers’ hands are clunky, when used in the proper amounts, and with clear purpose, work exceptionally well.

Top Three (in no particular order) Three Page Openings From Fiction Published in April 2025

#1: Mystery Over Information

The Cat Who Saved the Library by Sosuke Natsukawa (translated by Lousie Heal Kawai)

The opposite of info dumping is creating mystery. What’s engaging about The Cat Who Saved the Library’s opening is that it is setting up a clear problem from the first sentence that’s more unique than just any old dead body: books have been disappearing. But crucially, the author is not in a rush to tell you exactly why or every little detail about its protagonist—and we don’t even see this “cat that saves the library” in the first three pages at all. Instead, we start to accumulate little interesting details about our problem and our character. We learn which books are missing, for instance, which offers some indecipherable but interesting clues. Notice, that the novel reveals the character’s age but told more subtly through her grade at school rather than coming out and saying she’s thirteen or fourteen.

The Cat Who Saved the Library is in the mystery genre of course, but really isn’t every piece of fiction a mystery? Isn’t the idea to get your reader to keep reading because they are curious, whether that’s about what’s going to happen next or when they’ll stumble across your next brilliant line, or what other essential truth they’ll gain from reading on? This novel has first-three-page opening moves that any writer can take note of— you have three hundred pages to get into it all, if it’s a good premise let it breathe with a focused, intriguing opening scene.

#2: Action With No Context

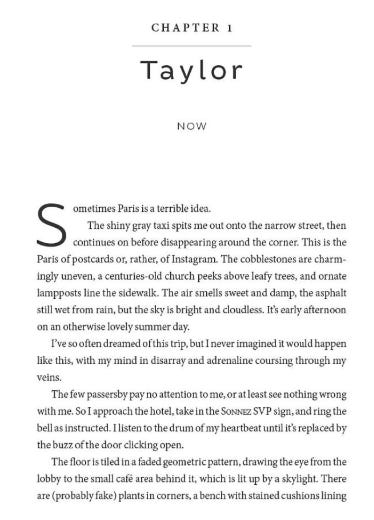

The French Honeymoon by Anne-Sophie Jouhanneau

A surefire way to make an impression in the first pages is to just pick a scene and show the reader some action with purpose. Contrary to using genre assumptions (aka tropes) to clearly define what kind of story we’re reading, if there’s an interesting piece of action, the writer doesn’t need to explain much at all. Similar to the next novel on this list, The French Honeymoon opens up with a killer Big Voice thesis statement but then dives right into the action, making us instantly curious who this woman is and why the Paris she is moving through is a terrible idea.

*I accidentally skipped the prologue the first time around. And since I’ve heaped praise on this opening, I also feel fine in telling you that this book has exactly the sort of useless prologue I’ve spoken about before— it’s basically an unidentified woman maybe or maybe-not drowning (body on the first page…).

Essay Style

Perspective(s) by Laurent Binet (translated by Sam Taylor)

Now that I’ve railed against the unnecessary fiction prologues plenty, Perspective(s) provides a counterpoint: a prologue/preface worth celebrating. The novel has an old-school style found manuscript opening, where the narrator tells you they discovered the book you’re about to read. Perspective(s) is an example of voice over gone right. What works is that the opening starts with one or two self-reflective “Big Voice” lines (“Let nobody say that I am incapable of repentance.”) and then follows these bits with tons of specificity. What follows is almost a personal essay on Florence, packed with detail, historical fact, observation, and arguments. The effect is that the novel opens forcefully, but contrary to common advice that’s given, it tells you absolutely nothing about the character or the stakes of the novel that follows. Instead, it dances around its subject and intrigues you to turn to the next pages to find out. And reading 100 versions of a three-page opening really gives you an appreciation for how many different ways and techniques there are to make the reader want to do just that.

If there is a three-page opening you think is great, whether it’s from a contemporary or classic novel, I’d love to hear from you in the comments—but sorry, there’s no $100,000 on offer if yours is the best.

Well, Moby Dick is pretty good.

I don’t always believe in Show Don’t Tell, but my Lord — “I’m a rogue and a reprobate”?? Imagine if that’s how Han Solo had introduced himself.

My favorite first person openings clue us to the personality of the character via their opinions. I love how much work Elif Batuman does in the opening to The Idiot. The way she’s casually dismissive of her dad saying he’d visited a museum via the internet. That opening didn’t blow me away at the time, but I really like that I never felt like she was showing off. The subtly and humor of the whole novel is present in those first pages.