Despite being a cultural product that doesn’t have as much economic value as television, music, film, or news, books remain an important cultural symbol. In the age of social media, books are just as talismanic as they’ve ever been. People use objects to represent their personality, beliefs, and opinions. Most recently, a slightly random psychology book with the perfect title for the moment, Inner Excellence, became a #1 bestseller and sold a quarter of a million copies when about-to-be Superbowl champion Philadelphia Eagles wide receiver A.J. Brown was spotted reading the book on the sideline.

When you devote a good amount of your time observing what people are reading, who they are, and what books they talk about, you start to notice patterns: some books come up over and over again. Here are a few very famous books and my ideas about what the people who wave them around or display them prominently on their shelves (or out at the café) are communicating.

Look at My Authority: The Bible

Honorable mentions: The Constitution; Other Major Religious Texts

It’s arguable that the origins of book publishing are just as wrapped up in the desire to spread knowledge as they are in using a book for grandstanding. I’m not going to go too far into the well of how major religious texts have been used as symbols to justify bad things, but let’s just say there’s a reason every post-apocalyptic novel features some sort of evil preacher. Serial killers on TV often like to pick the scariest Bible verses to justify an elaborate murder. It’s one of the few books that people actually wave while talking. Claiming to have read the Bible back to front or quoting it from memory are probably two of the oldest tricks for people trying to convey their authority.

Bonus points for other major religious texts as well as our trusty Constitution, which politicians in particular have made a show of carrying around in pocket-sized form, regardless if they plan to trample on those rights and ideals or not.

The A+ English Student: To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Honorable mentions: The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald; Anything by Jane Austen

We’ve been through this before, but every time a big “best novel ever” list comes out, To Kill a Mockingbird is reliably top of the heap. Millions of people read it in U.S. schools, and it acts as a formative moment for many readers (that formative moment mostly boils down to a realization: “books can be good!”). Then those readers likely go on to read Gatsby (also reliably top ten), Austen, and sometimes eventually become English teachers themselves or end up working in publishing. Pets and children get named Scout. These are great books, but there’s no reason to stop developing your taste (or personality) after high school.

“Free Thinkers” Who Hate Taxes: The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand

Honorable mentions: Every Other Ayn Rand Book; Common Sense by Thomas Paine; Walden by Henry David Thoreau

Mark Cuban has become somewhat of the people’s billionaire in recent years, finally criticizing the Luka Doncic trade and, nearly as importantly, starting a public benefit company that tries to reduce the cost of generic drugs.

What type of person says they read Ayn Rand? Once on Shark Tank Mark Cuban said The Fountainhead was one of his favorite books. As a result, the rumor follows him everywhere that he owns a 300-foot yacht—which boasts a full-sized basketball court—that’s named after Rand’s book. This is not true, but it doesn’t stop it from feeling so true that it generated two dozen fake headlines from reputable news outlets at the time.

In other Ayn Rand related nonsense, I’ve read part of Atlas Shrugged because a fairly large southern bank donated a chunk of money to my college as long as my college agreed to subject its economic students to the torture of Rand’s trashy-soap-opera-cum-thinly-veiled-ideological-fever-dream that is her “novel” on free market capitalism. It’s weird how the people with all the money love these books and crave this type of “freedom,”which, to be clear, is just the freedom to keep their piles of gold free from taxes.

Insufferable Intellectual Men: Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace

Honorable mentions: Anything by Thomas Pynchon (but especially the thick ones); Anything by Haruki Murakami (but especially 1Q84); Ulysses by James Joyce; The Power Broker by Robert Caro.

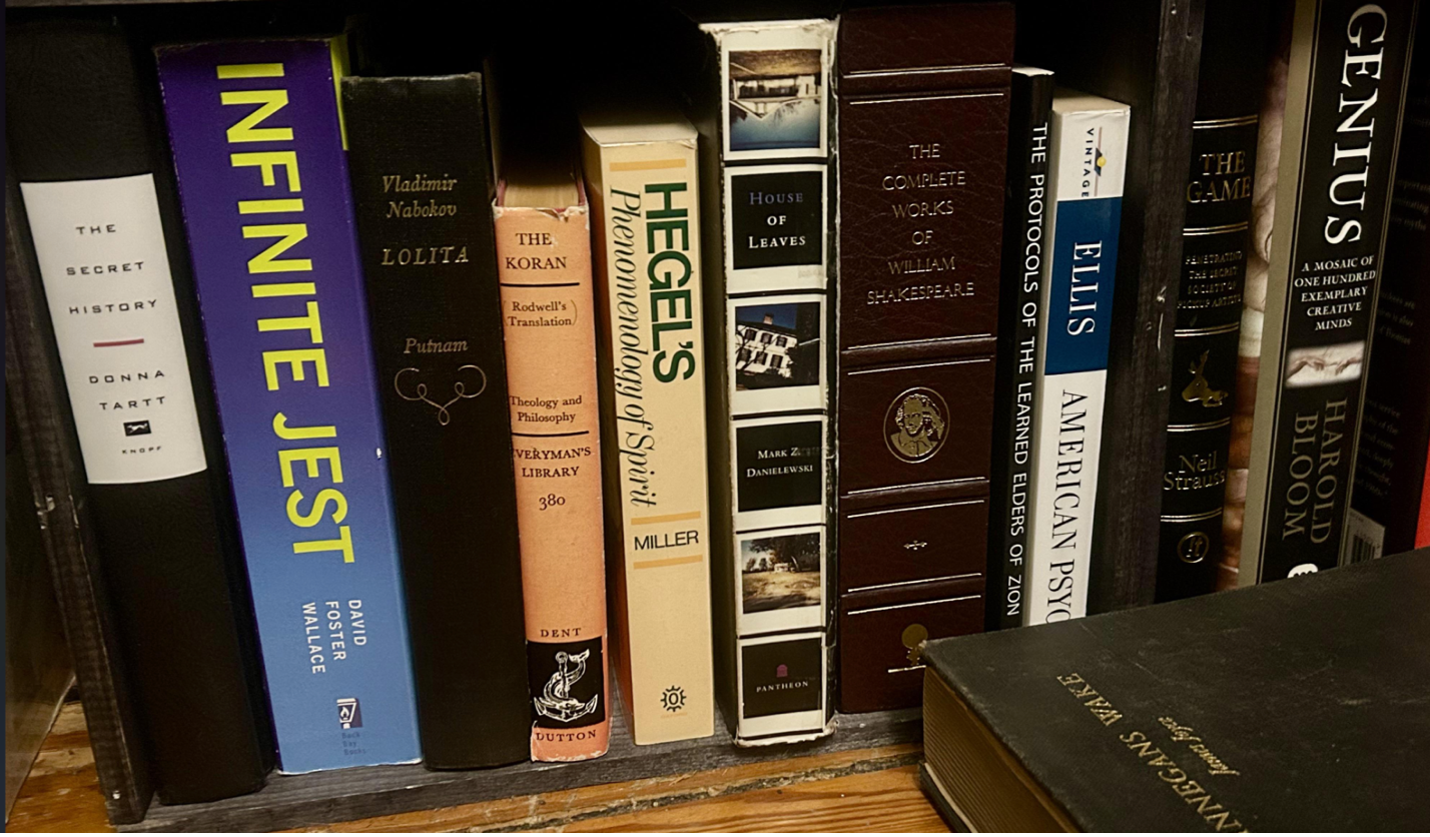

A popular question on Reddit is “What does my bookshelf say about me?”. And I’d say Infinite Jest is such an obvious tell of a certain type of person (usually male; odds are they are insufferable about whatever their field of expertise is) that it seems a lot of people on Reddit are just posting shelves with Infinite Jest to wind people up. After scanning through some of these shelves I confirmed one of my other honorable mentions Pynchon, who is the forefather of David Foster Wallace intelligentia-obscura-maximus (I never studied Latin if you can’t tell). Alas, Murakami is often right alongside Wallace and Pynchon. These three represent the male literary starter pack, and kudos to these readers for picking up something challenging and actually good, but I’m here to let you know—fellow insufferable men—that it’s also okay to read three 300-page novels rather than some pretentious mega tome.

Next-level highbrow literary and insufferable men mix this up with either Ulysses or The Power Broker, the latter of which was a pandemic mainstay for TV talking heads.

Walking Red Flags: Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Honorable Mentions: 12 Rules to Life by Jordan Peterson

I was just going to show this picture and leave it at that…

Lolita is probably so famous because its origins are in being taboo, banned, and censored. Many have picked up the freedom of expression mantle when extolling their admiration for the novel. But even if Cooper and Waterhouse were reading Lolita in the park knowingly as a joke, it feels a bit like a Woody Allen movie doing all sorts of entertaining gymnastics to justify something icky.

Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules to Life is a good analogy here. Not in any sort of literary sense—at least Lolita displayers have the incredible prose of Vladimir Nabokov to legitimately fall back on. But 12 Rules is similar in that it often masquerades as one thing, a self-help book, while taking on an entirely different meaning when someone puts it on a prominent place on their bookshelf. Peterson’s disturbing lobster metaphor (TL;DR: essentially men should be at the top of a hierarchal society, um “naturally”, because that’s what lobsters, an animal without a brain, evolved to do), which he sells merch off of, tells you that people are more about “men’s rights” who display Peterson than making their bed.

Everyone Finds Out They Are Special and Unique in the Exact Same Way: On the Road by Jack Kerouac

Honorable Mentions: Eat, Pray, Love by Elizabeth Gilbert; Under the Tuscan Sun by Frances Mayes

No book is responsible for more memoirs written by men in their 20s than Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. This Beat Generation classic has probably been such a powerful book and symbol for so long because it takes extremely common experiences — road trips, bumming around with your friends, and learning about adult life — and gives readers permission to see these and events and their young lives as deserving of the grandeur and awe we feel at these ages. Ditto is the effect— although for an older, more female audience—of memoirs Eat, Pray Love and Under the Tuscan Sun. Traveling is amazing, you learn a lot about other people and yourself—tens of millions of Americans do it every year. To be fair you could include any number of iconic memoirs written by non-famous people in this category— their primary function might be to inspire us to see our common experiences as a little bit more special.

Wannabe Masters of the Universe: The 48 Laws of Power by Robert Greene

Honorable mentions: The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli; The Art of War by Sun Tzu

The Prince far precedes The 48 Laws of Power (we’re using Wiki links rather than retail links for these because you really shouldn’t be buying them) in this category, such that the guy who wrote it became an adjective. The Art of War was written in the 5th century and has been gracing the bookshelves of business executives and other white-collar workers residing very far away from the fields of battle for many decades. But 48 Laws (it must be admitted that The 48 Laws of Power is an absolute G.O.A.T book title contender, which probably accounts for a lot of its success) is the latest iteration and the talismanic book I’m seeing with more frequency than either of its predecessors these days. On the subway. Out with the populace. As I understand it, The 48 Laws of Power is basically a big recycling project of other Wannabe Masters of the Universe books—a “48 Laws of Power Reading List” on Goodreads created by user “Hitler” (2 Books rated, 0 friends), includes Machiavelli’s The Prince. 48 Laws is so generally popular that 50 Cent co-authored a spinoff, The 50th Law, with Greene. If this person asks you for a business investment or to go on a date or to sign their petition, think twice or just run in the opposite direction.

Final Thoughts

This is not to say that you shouldn’t read or own any of these books (okay, some of them, I am saying you absolutely shouldn’t read or own), but just beware of what they communicate and take caution to not fall into cliché or start a cult or date someone in college seventeen years your junior or buy a scarf with passages from To Kill a Mockingbird on it (hey, I’m not saying every book is equally dangerous).

To show this was a light-hearted exercise these are on my bookshelf (although the copy of Infinite Jest is my wife’s!). We can all poke a little fun at ourselves and feel secure, as long as we don’t own the complete sixteen book set of Ayn Rand. Also, it’s worth noting that these are on the tippity-top shelf, safely above eye level.

This was so much fun to read, and thanks for the rabbit-hole Reddit link :)

The thing about LOLITA is that most people misinterpret it. It begins with a foreword by a fictitious psychologist (the author in disguise) straight up saying that this is a tragic book and the narrator is a monster. From there, the reader is left to choose how they’ll respond to the book. Will they give in to Humbert’s suave persona and smooth voice, believing everything the says? Or will they look past his hand-waving to see what’s actually quite obvious and plain: the victim’s suffering?

Nabokov himself was the victim of sexual abuse when he was a child, which I’m sure must have influenced his desire to tell this story, and to tell it in this particular way. It’s a very effective work of art in that way too many readers get sucked in by Humbert’s manipulation and see it as a “taboo love story” when the author clearly intended it to be a mirror held up to the reader, to face the question of whether we even see victims in this culture, or whether we choose instead to believe whatever stories we’re told.

Red flag, though? I think that depends on why it’s on the bookshelf, which you can only discover by talking about the book with the owner of that bookshelf.

100% agree on THE FOUNTAINHEAD, though. Girl, run.