Boomer’d

Submissions and the art of giving up at the right time

“This is aw-ful.”

We are approximately 4-8 minutes into a feature-length film. Barely anything has happened yet. But one of the audience members is already convinced that we will not be finishing the film. The movie has been Boomer’d. To Boomer something is to give up on it exceedingly early and pass down a judgement, based on very little, that is as certain as it is swift.

This is not to pick on the older generation — okay, it kind of is, as they are the reason for the term’s origination. But just like Boomers are as distracted by cat videos and TikTok as 20- and 30-year-olds are, Boomering isn’t just for the 60+ crowd. For the Millennial or Gen Z generations, “giving up” on a movie might take the form of scrolling through social media for the duration of the film rather than loudly complaining—and yes, they are a little more distracted than Boomers by virtue of having lived their entire lives with the internet and cell phones.

But really the term can be jokingly employed to poke fun at anyone for being quitters, demanding that they instantly like something from minute one, and falling prey to short form video scrolling brain. Watching the recent Netflix film It’s What’s Inside, the whole group I was watching with was a little on guard during the first 10 minutes— the rotating 360 camera and nauseating quick cuts almost got the film Boomer’d. Then the camera settled down and the film turned out to be a really well acted, well made, and refreshingly original thriller/speculative/horror romp. Gutting through the first 10 minutes of It’s What’s Inside is a good example of why it’s necessary to stick with art sometimes when you aren’t “feeling it”. Yes, someone in our group said “the camera better not be like this for the whole movie,” but they didn’t ask to turn it off and so we kept watching. And yet, this is also true: if the movie had continued for another 20 minutes with the camera panning like the old-school IMAX intro where you fly around in the POV of a helicopter pilot, then it would have been silly not to give up on it. Giving up is the right thing to do sometimes, but Boomering is about giving up too early.

Book Submissions and When to Give Up

Increasingly my life as an editor has become more consumed with book submissions. These are the potential projects editors read to decide if they want to try to acquire, edit and publish them. (Even if an editor likes something they read, they don’t have the automatic green light to buy a book; even if they get the green light, they aren’t always successful at buying a book, they can lose the book to another house in a competitive buying process).

Full-time editors get about a submission or more a day from agents — that’s 365+ a year. To put this in perspective, even the most avid of readers out in the wild probably read a book or two a week at most (50-100 books per year maximum), and that’s on the extreme end. Along with editing (where you read a full manuscript anywhere from 2-10+ times), reading competitive books (for fun), and all of the non-reading work that goes into being an editor (meetings, phone calls, writing sales materials, admin, production, emails, emails, emails), there’s simply not a way to read every submission nose to tail.

Thus, the art of reading over 300+ submissions a year is one of giving up. The real fight being for an editor not to Boomer a submission before it gets off the ground. While yes, many editors, literary agents, and readers will tell you they can know something isn’t good or isn’t for them in just a few pages, it’s important to resist the impulse to complain loudly and throw a submission in the recycle bucket after chapter 1.

Can you truly know in a couple pages if something is good or bad? Of course you can. Sometimes you can know by the subtitle of a nonfiction book, the choice in character names, or the opening few lines the quality of a submission and whether or not you will like it. We were not sure if I’m Thinking of Ending Things was a good movie to watch over the holidays with family within the first three minutes, and we were entirely correct. But that doesn’t mean you should give up right then and there. Since it’s too mean and incredibly dubious to post any real examples from submissions I’ve received in my day job, let’s give an example in the reverse. As it is also equally true that a great book signals to you from the earliest pages that it is great in much the same way a mediocre one does.

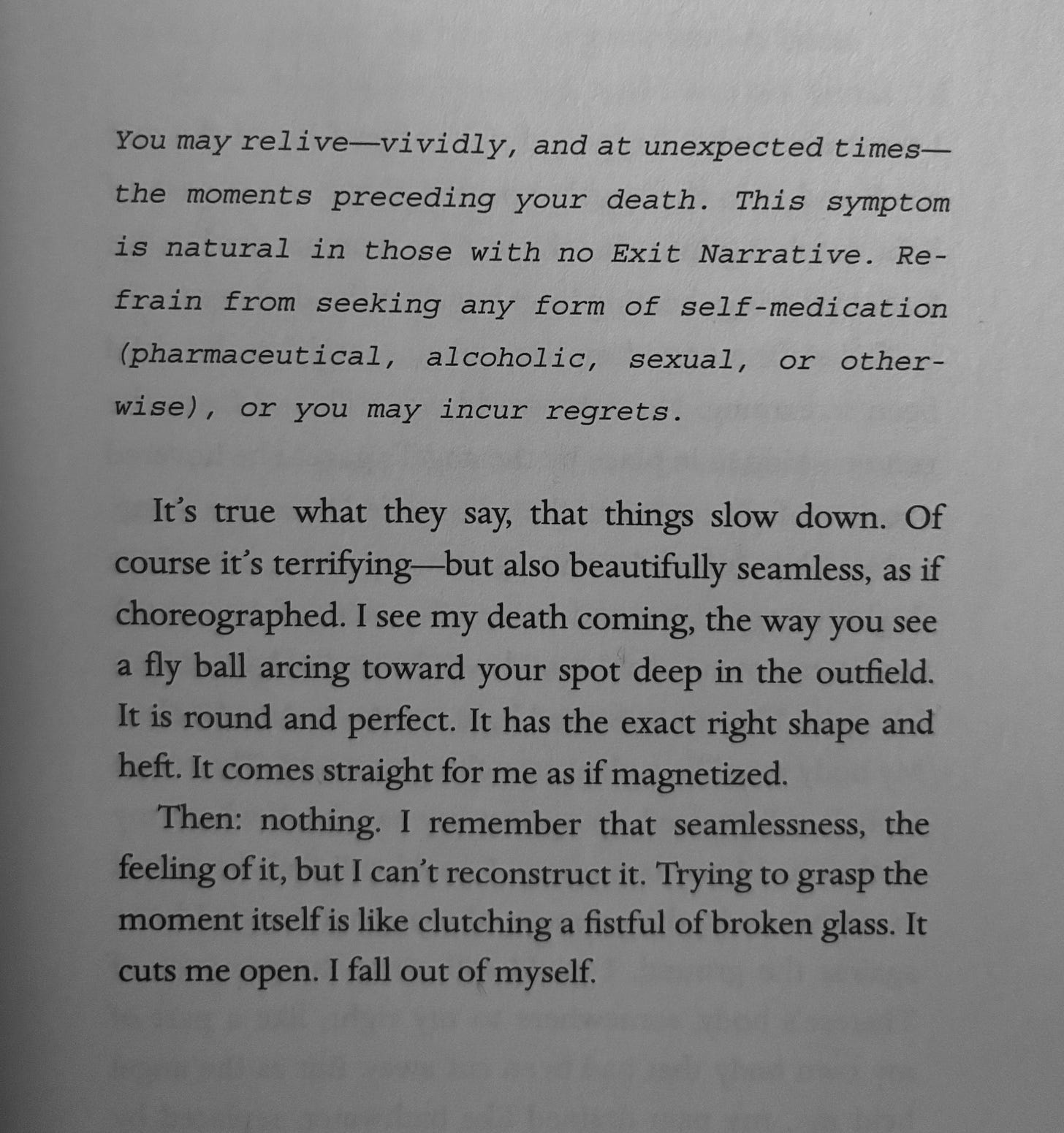

Here’s the opening page of The Regrets, an under-read book I constantly love to plug. I remember reading this in a bookstore and knowing the writer had me in the palm of their hand from this first page:

This is a perfect opening. In fact, I bought the book reading just this page alone in the bookstore. Just as easily I could have reversed Boomer’d myself (we’ll need to workshop a term for that) here and purchased a book I didn’t end up liking. Thankfully, the rest of the book did turn out to be fantastic and these exceptionally straightforward, carefully chosen, but completely surreal sentences did portend what was to come.

Still, for time-saving reasons, many seasoned editors will advise you to stop when you know you aren’t going to try to buy a submission, the second you know it’s “not for you.” This is reasonable enough advice in the realm of efficient time allocation: why spend more time on something you’re not going to work on over something you have to work on? But this is not my rule because inevitably it leads to shutting the door and closing your heart even more quickly than we naturally already do.

Editors —of all ages, I’m truly sorry I made this term so agist the longer this goes on — often practicing Boomering before they even read a page, saying things like “I don’t read books with tall characters” or “mysteries with attics really aren’t working right now.” I never have these strictures because I’m often proven wrong whenever I Boomer with arbitrary criteria. I was annoyed for a while by novels about writers set in New York — there are so many, and hasn’t it all been done before? — but then two of my favorite books I’ve ever worked on turned out to have quite a lot to to with writer characters in New York and the process of writing. It seems like there is no end of World War II novels, but if an editor swore them off entirely they might miss out on the next White Teeth (which has a sneaky big WWII plot even though people forget about it) or All the Light We Cannot See.

Writers and their literary agents work very hard on the submissions they put forth, and while there is no feasible or sane way to promise that you will read everything in its entirety, it is important to give as much as you can for them and yourself. For an editor, and this really applies to any regular consumer of art (of any age), you shouldn’t quit the second you aren’t “feeling something” but maybe a few seconds, minutes, or hours after that, when you realize why you aren’t feeling something. Don’t simply say something is awful five minutes in and queue up the next season of The Great British Bake Off as a safe palate cleanser. Usually, your instinct is right and you won’t like a book, a film, a song that you don’t like the start of, but it’s worth the rare chance that you do. More so, it’s worth sticking it out to understand why you don’t like something or don’t want to watch it for practical reasons (i.e. “this show is okay, but do I really want to watch 8 more episodes simply because I started it?”), rather than treating something as difficult to make as a book or a movie like it is supposed to be mindlessly consumed or checked off a list. That way you learn something out of the process rather than wasting time.

So next time, Boomers, say “this is aw-ful…because the camera keeps shaking like we’re in a hurricane” and then we’ll gladly find something else to watch.