Daunting Classic: A YA Novel with Human Sacrifice?

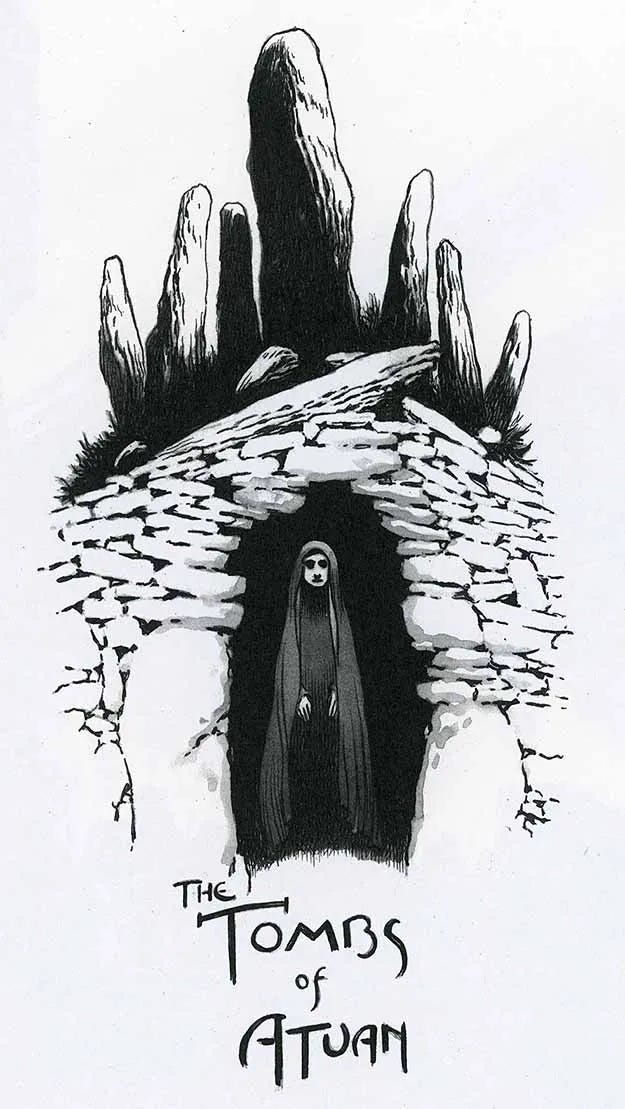

Earthsea Book #2: The Tombs of Atuan by Ursula K. Le Guin

What Content Should Kids be Allowed to Consume?

For as long as I’ve been alive the moral panic over what kids can and cannot consume has raged strongly in American culture. For me, as a teenager, it was all about music, specifically rap music with its sexually-charged, violent, and misogynistic lyrics. As anyone who has been a teenager can attest to, this backlash and concern from parents did nothing to slow down my love of rap music and probably accelerated it, if anything. Now, I look back on the fact I got my hands on Snoop Dog’s Doggystyle CD at twelve and am slightly horrified by the cover art and insert this album had (think a dirty version of Dogs Playing Poker). Why did I gravitate toward this album as a young person? Snoop was 22 when the album came out. Gin and Juice and its music video are about Snoop having a house party while his parents are out of the house. Sans adult content, there is a lot about rap’s rebelliousness to its funky choruses that appeals to kids— I mean, the song literally has “juice” in the title (in many ways, the rappers of the 90s were part hardened gangsters and part not-quite-grown-up kids).

In 2025, restricting content for kids is back in a stronger way than ever. You have a small vocal minority (to cite the linked article “11 people [are] responsible for 60 percent of filings nationwide” on library book bans) fear mongering against kids learning about gender and sexuality. There is a separate — although seemingly more muted now that the political tides have shifted — but related concern about introducing kids and young adults to the negative sides of racism and bigotry. Years ago, we were talking about the retroactive sensitivity edits made to Roald Dahl’s novels meant for young adults. The underlying argument from each camp is that showing kids these things will become learned behavior (making the former group’s motivations much more sinister it must be noted).

Human Sacrifice and Slavery

In steps Ursula K. Le Guin from nearly 60(!) years ago to boldly say “the kids are alright.” In the first Earthsea novel Le Guin, a white woman, made her protagonist a dark-skinned boy. And although Le Guin doesn’t eschew violence in her fantasy world—the protagonist is beaten by his father and fends off a pillaging army in the first few pages of book I in the series— her stated goal was not to use war as The Wizard of Earthsea’s narrative engine.

In the second Earthsea novel, The Tombs of Atuan, Le Guin arguably ups the ante to subvert traditional fantasy story and theme, and fly her flag in the face of content warnings for kids. The Tombs of Atuan, begins with a young girl who is chosen to become the high priestess after the last high priestess has died, very much echoing the process for how the Dalai Lama’s successor is chosen. The high priestess is charged with looking over the Tombs of Atuan, and her job is basically to keep The Gods — the Nameless Ones — happy in the old-world sense. The Tombs of Atuan begins with the girl who is chosen to be the next high priestess almost being beheaded at the sacrificial altar/throne (a fair primer for the practices of the religion the child will become the figurehead of):

Alone, the child climbed up four of the seven steps of red-veined marble. They were so broad and high that she had to get both feet onto one step before attempting the next.

On the middle step, directly in front of the throne, stood a large, rough block of wood, hollowed out on top. The child knelt on both knees and fitted her head into the hollow, turning it a little sideways. She knelt there without moving.

A figure in a belted gown of white wool stepped suddenly out of the shadows at the right of the throne and strode down the steps to the child. His face was masked with white. He held a sword of polished steel five feet long. Without word or hesitation he swung the sword, held in both hands, up over the little girl's neck. The drum stopped beating.

As the blade swung to its highest point and poised, a figure in black darted out from the left side of the throne, leapt down the stairs, and stayed the sacrificer’s arms with slenderer arms. The sharp edge of the sword glittered in midair. So they balanced for a moment, the white figure and the black, both faceless, dancer-like above the motionless child whose white neck was bared by the parting of her black hair.

From there, Le Guin does not ease up. One of the first tasks Arha, our new high priestess, must deal with is the prisoners trapped in the domain she now oversees. These are unanointed people who have wandered into the tomb (an underground maze that Arha must navigate in complete darkness) and therefore by rule can never leave. This scene, I can confidently say, both in terms of subject and weightiness is not one most YA fantasy authors would dare to write today:

She went a little farther into the room, hesitant, peering through the smoky haze. The Prisoners were manacled by both ankles and one wrist to great rings driven into the rock of the wall. If one of them wanted to lie down, his chained arm must remain raised, hanging from the manacle. Their hair and beards had made a matted tangle which, together with the shadows, hid their faces. One of them half lay, the other two sat or squatted. They were naked. The smell from them was stronger even than the reek of smoke.

One of them seemed to be watching Arha; she thought she saw the glitter of eyes, then was not sure. The others had not moved or lifted their heads.

She turned away. “They are not men anymore,” she said.

“They were never men. They were demons, beast-spirits, who plotted against the sacred life of the Godking!” Kossil’s eyes shone with the reddish torchlight.

In fact, we know that a modern author likely wouldn’t ever put something like this in their novel—considering YA author Amélie Wen Zhao actually canceled publishing her own book Blood Heir, which included a depiction of slavery that the vocal part of the online YA community deemed harmful content. (It is impossible to analyze these claims here because the book was never published and even the many articles discussing the incident don’t quote the novel directly.)

Meanwhile, in Le Guin’s book written in 1970, Arha, her teenage protagonist, the character we are generally supposed to sympathize with, then contemplates how she will kill these enslaved people. Arha herself, the supreme authority, commands that they be left to die of thirst and starvation in total darkness as a sacrifice—and, spoiler, that happens!

Le Great Storyteller

You might be forgiven for thinking that Le Guin, who puts her moral positions so nakedly out in the open, would be the sort of hippie-dippy writer who would never subject teenagers to such human darkness as a young girl torturing enslaved people to death. But that’s what is to love about Le Guin — she has such clear moral good in her heart and imagination, but she’s not about hiding and covering up human cruelty or nature to make her point.

Good people don’t positively contribute to the world by ignoring its awful happenings, but by confronting them. That’s what the rest of the second Earthsea novel is about. Arha, a girl we have seen be led down the darkest possible path, grows up and widens her aperture. There is a lot of hope and beauty in this novel beyond its dark beginnings. The Tombs of Atuan is a novel about discovery; that the claustrophobic maze that Arha has literally and metaphorically been confined to does not contain all of her possible choices as a person.

Le Guin is a masterful moral storyteller because she does not say “do this” or “don’t say that”, like it seems many people think fiction should do. Le Guin is not going to exclude sexuality or racism or forgo using the color black as a symbol for death or despair (see again: Roald Dahl edits) from her stories to “protect” her readers or young readers. Instead, The Tombs of Atuan is a story that says you don’t have to be born in the right circumstance, always use the right words, and never do a terrible thing in order to change as a person and make up for past transgressions. Le Guin never lies to the reader about the world to prove her moral stance, but shows us the possibilities of choosing something different within our realities.

What is Age Appropriate?

The truth is that 90s rap and violent video games (the other major scare story my youth) did not do lasting emotional damage or permanently shape a generation’s behavior for the worse. From the cover art to the lyrics, probably 70% of what was happening on Snoop’s debut album went over my head. Kid’s brains are more like cheese cloths rather than sponges when it comes to “harmful” content — or really any content.

Kids can enjoy Gin and Juice for its exquisite funk and the undeniable smooth flow of Snoop and also come to appreciate, as they become adults, that the cover art is kinda weird and 90s rap attitudes towards women were extremely flagrant. Blood Heir should have been published almost no matter how wrong it got its subject matter on an intellectual level. Even attempts at art that are far more misguided, less skillful, or incredibly morally uneven than Le Guin’s work are adding something to the conversation if made in good faith. We have to be exposed, safely — like, say, by reading words on a piece of paper! or listening to a four-minute song — to content “above our years.”

Many kids for instance seek out the macabre of Stephen King or horror movies. Similarly to how the true crime viewership is predominately female, as young people we often seek out what is dangerous, what we fear, or can’t wrap our heads around. Nothing we encounter between the pages of a book is nearly as terrifying as its equivalent real life experience, and certainly not as traumatic as witnessing what can be found on the internet or social media mere clicks away. We read and listen to start to understand, like Arha fumbling her way through her underground labyrinths. For only in understanding can we choose to do what is right.

Tombs Of Atuan is one of my all time fav books, partly for these reasons. Did Blood Heir only get (delayed) released in the UK - I've read it & can see it's available here so I assumed it was released widely. I have...opinions about the very American-centric criticism is received so I was glad AWZ got it out there in the end