Every reader has a set of idiosyncratic tastes. Kinds of settings they prefer. Characters they like. Genres they gravitate towards. Writing styles they adore. And on and on. Read more and you begin to swear against certain things at all cost. Cities you’re tired of reading about. Voices you find grating. Genres you won’t touch. Punctuation choices you roll your eyes at. As an editor or avid reader, you enter a third and final stage as a reader: the realization that there is an exception to nearly everything you thought you preferred and everything you premeditatedly disliked.

For a time, I was hell bent against New York novels. I’d read a lot of seriously great ones and found that a lot of the submissions or contemporary attempts at tackling this vaunted, much-picked-over city were pretty frequently just okay. The novel that broke the spell was one I read on submission for my boss at the time Cobble Hill by Cecily von Ziegesar. This novel had so many elements that are still unexciting to me on paper: an upscale neighborhood in New York; roman à clef-feeling characters; a plotline revolving around a writer.

Yet as idiosyncratic as readers are, writers are just the same. The choices that von Ziegesar makes from the first chapter dispel the notion that this is your typical upper crust New York novel or written by a younger novelist who read Jay McInerney, moved to the big city and wrote about their misadventures. It’s an amazing book about parenthood, middle-age ennui, teenagers, flesh and blood artists. To top it off, the writer character I was wary of is one of my favorite depictions of the absurdity of the nuts-and-bolts of the creative writing process.

What may appear as cliché or familiar on the surface can be dispelled fairly quickly if you remain open to being wrong. For as picked-over as New York is, it will never run out of storytelling possibilities. Cobble Hill has a sense of humor completely its own and each character is so deeply observed and occasionally weird. None of it feels borrowed from other New York novels.

Cobble Hill was the submission that put me on the path to stage three of reading: there’s always an exception. A book should (of course) be considered on its full merits, not its elevator pitch. But also, there is the reality to contend with that there are unlimited books but not unlimited time to read. That said, as an editors gets into a manuscript, (or a reader get into a published book, there are a few flags, red ones that tell you to run for the hills early, yellow ones to approach with skepticism, and green ones to drop everything to turn the pages.

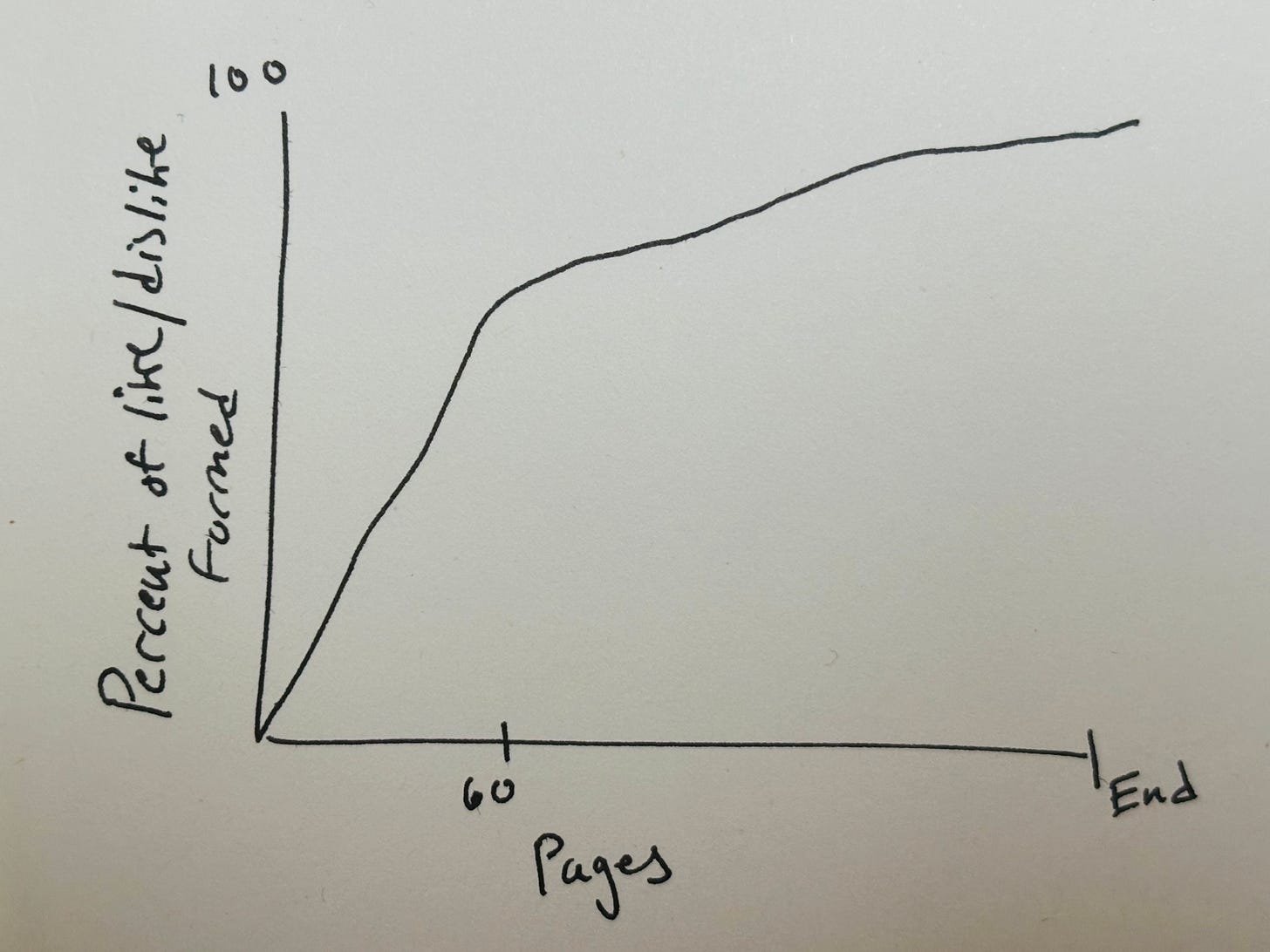

Red Flag #1: A Hum-Drum First 60 Pages

Everyone has their own arbitrary cutoff line for giving up on a book. Sixty pages feels like a fair amount to give to a book if you’re coming in cold. Sixty pages gives the writer a chance to develop more than just the opening. If you go by only the first ten, fifteen, or even twenty pages — as some advocate for — you risk giving up on a writer trying to try a more subtle opening, multiple characters, or subverting your expectations. At sixty pages, you can maybe form an opinion with 60-80% accuracy.

I can count on both of my hands how many times a book or manuscript has raised my opinion from poor or middling to good or great after sixty pages. If you’re decidedly a Finisher, this doesn’t mean you aren’t going to find something to appreciate if you read to the end of a book with curiosity (a lot of the reading editors do, and probably regular readers, too, is to understand why other readers like something so much…*cough* Fourth Wing *cough*).

There are plenty of reasons to ignore this red flag. If the book is recommended highly by someone you trust; if it’s an author you love and want to understand their whole career; if you feel the need to see how a writer lands the plane even if you don’t like the way they’re flying it.

P.S. One of the novels that I can count on two hands that defied the sixty-page rule is The Book of Night Women by Marlon James. A slow burn of slow burn historical novel that won me over in a big way with its crescendo. I kept reading probably because I wasn’t an editor yet and because I loved James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings so much.

Red Flag #2: Unreasonably Lofty Comparisons + General Stats

A risk-free investment with 15% annual returns, instant weight loss with no side effects, a product that will make great novel writing as easy as typing a Google search. In the age of disinformation, every school should require to hanging a “too good to be true” sign in classrooms. And it’s no different in books. If an agent tells me they have “the next Dan Brown” it is easy to read this the same way you might read the Wikipedia entry for “List of dates predicted for apocalyptic events.” Lofty or discordant comparisons for fiction often mean someone doesn’t quite know what they have or the book in question doesn’t inspire enough to necessitate more than a first-thought comparison. The cousin to lofty comparisons are general stats— a particular scourge of proposals for nonfiction books. A readership for a music book is not hundreds of millions of Spotify users. Stats like these are a red flag for their delusion, if a writer or literary agent sees their addressable readership as a bigger audience than any book has ever sold in past decade, point them toward your new sign and put it at the bottom of your reading pile.

Red Flag #3: Commercial Cynicism

Here’s a not-so-secret secret: most of those annoyingly broad, seemingly lowest-common-denominator novels that you love to hate are not written by cynical writers who were just looking to get rich. Brandon Sanderson might be rightfully roasted, but he can’t be criticized (in my opinion) for insincerity.

There’s no bigger red flag to me as an editor than when I can tell a writer is behaving cynically for sales purposes. Romantasy might be the latest gold rush, but I guarantee that good editors in that category can root out most writers that think it is a frivolous genre but are looking to cash in. There’s no secret that this is largely an issue in genre, but whether it’s a cozy mystery or World War II novel or speculative thriller, a dispassionate, cold approach to writing for money will always come through on the page. The emotions feel manipulative and overly planned, the humor flat, and the distain of someone who believes they should be writing a literary masterpiece instead usually is quite clear from the writing. Yes, a few slip through here and there, publishers pay large sums for a good one-liner occasionally, but it’s extremely rare that these mercenaries find long term success. Plus, if you’re going to sell out, do yourself a favor and choose something more lucrative and less labor intensive than writing a book.

Yellow Flag #1: Prologues (in fiction)

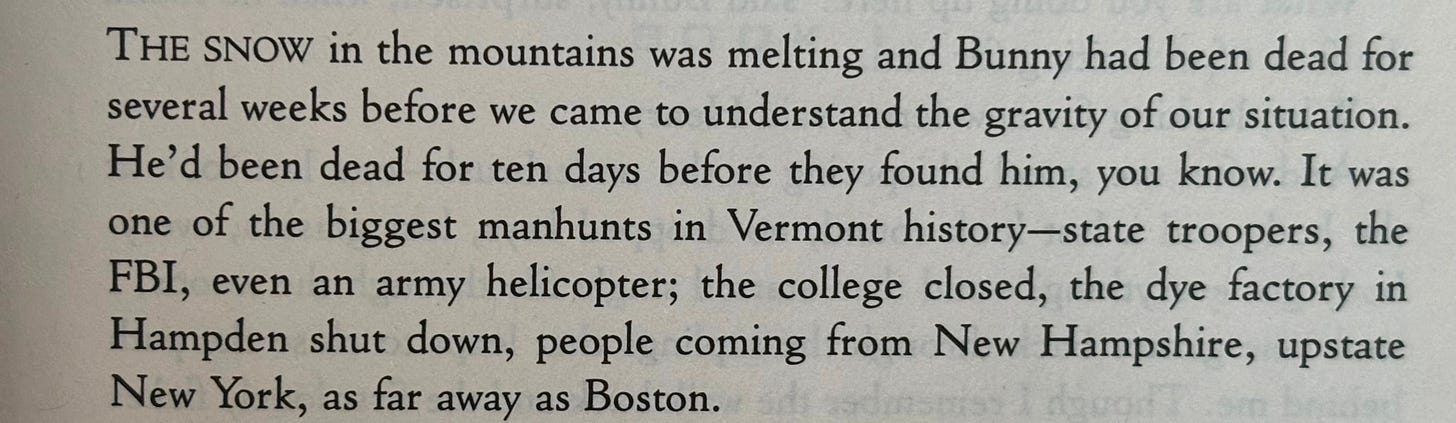

Most novels don’t need a 2-page coda. This flag mostly comes up in literary novels, and the blame can be placed almost entirely (in my humble opinion) at the feet of Donna Tartt’s The Secret History. Tartt extra popularized the notion to “put a body on the first page” for literary novelists by putting the body in the prologue and subsequently ignoring it for hundreds of pages. If you’re not Tartt, don’t try to cheat the reader and inject a false sense of plot or theme right off the bat, a two page prologue is rarely “doing the work.” An ambitious, declarative prologue (they usually run 1-2 pages) is not going to disqualify a book, but it doesn’t always start things off on the right foot.

Yellow Flag #2: More Marketing than Material

The name of the game in book publishing is platform…supposedly. But a deluge of marketing, social media, and industry connections often raises suspicion not excitement (in my book). Honestly, even when I see a published book with several pages worth of praise from reviewers, it has the opposite of the intended effect on me. I start to think the writer must have had connections based on where they went to school, who they know socially, what writing program they attended, etc. The material itself should always take the spotlight over marketing, whether we’re talking about a yet-to-be-published book or a bestseller. It’s a yellow flag when marketing seems to be running interference for a product that’s so-so (less is often more).

Yellow Flag #3: Category Matters

I take a fairly agnostic approach to genre and category as an editor and yet it is unquestionable that the type of book matters when judging how likely a reader is to like it. Last year, I asked the question “What is the hardest kind of book to write?” and did a March Madness bracket answering just that. Spoiler: I decided that short story collections and memoir have a higher bar than other categories of books. That means those types of books have to be exceptional in an absolute sense for lots of people to read and like them. All kinds of categories and subcategories and genres are yellow flags and they change over time as tastes and forms change. Westerns used to be easy, now it would have to be exceptional or couched in another genre to pass muster. There will always be more room for error in a murder mystery than there will be for the next great American novel.

Green Flag #1: Passionate Descriptions/Pitches/Reviews

A pitch is a helpful framing device for editors and readers. A great pitch can’t transform an okay book into an exceptional one. But by the same token a disastrous pitch won’t ruin a book of undeniable genius. At their best, a book pitch accentuates what is exceptional and draws even more attention to it. A good description or pitch is not deceptive sales-speak, but a massive green flag you should heed and run toward as a reader.

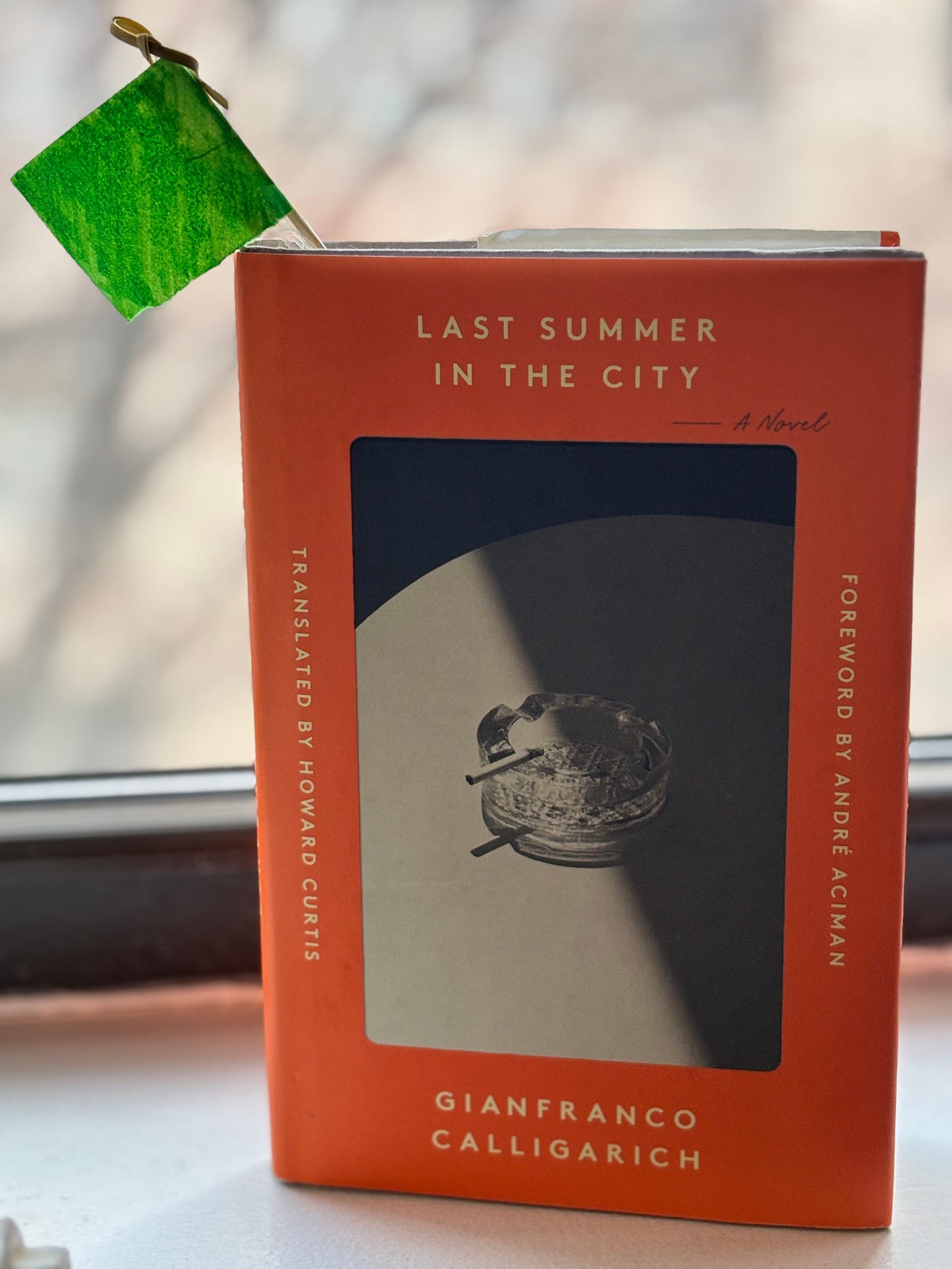

Genuine excitement and belief always comes through. If a book’s description, review, or pitch is vague and/or flowery it is more likely to be a mediocre book. When literary agents, editors, readers, or reviewers really connect, I find they start to almost inhibit the tone of the book itself in their descriptions. Here’s a great description (online on the back cover) of a novel that I’ve read almost once a year since discovering it Last Summer in the City by Gianfranco Calligarich (translated by Howard Curtis)

In a city smothering under the summer sun and an overdose of la dolce vita, Leo Gazarra spends his time in an alcoholic haze, bouncing between run-down hotels and the homes of his rich and well-educated friends, without whom he would probably starve. At thirty, he’s still drifting: between jobs that mean nothing to him, between human relationships both ephemeral and frayed. Everyone he knows wants to graduate, get married, get rich—but not him. He has no ambitions whatsoever. Rather than toil and spin, isn’t it better to submit to the alienation of the Eternal City, Rome, sometimes a cruel and indifferent mistress, sometimes sweet and sublime? There can be no half measures with her, either she’s the love of your life or you have to leave her.

First discovered by Natalia Ginzburg, Last Summer in the City is a forgotten classic of Italian literature, a great novel of a stature similar to that of The Great Gatsby or The Catcher in the Rye.

Okay, forget what I said earlier about lofty comparisons—or at least know, there’s an exception to that rule, too.

Green Flag #2: A Sentence You Want to Read Out Loud

A common cliché editors and readers perpetuate is that you should be gripped from the first page or chapter. That’s a little much, although sometimes it really is the case. Instead, usually within the first sixty pages of a novel you’ll end up finding you love a particular turn of phrase, image, or sentence that makes you sit up or shout it out loud to a person in another room. And if that happens, there’s usually much more great stuff to follow.

Word of caution: this does not necessarily mean a sentence that is poetic or philosophical (discount those a bit), but more so a sentence that’s unique because of its perspective or surprise (go read that The Secret History’s prologue again and you’ll see it’s the voice Tartt is developing not linguistic pyrotechnics that make her opening standout).

Sometimes kismet happens and the first line accomplishes this, as it was for me with The Payback by Kashana Cauley:

In the handful of minutes before our store opened, the sales day was pregnant with potential cash.

“Pregnant with potential cash,” I still think about the way that rolls off the tongue after reading this novel a half dozen times, it made me sit up, take notice, and lock in. Distinct sentences like these constitute a green flag that is rarely ever wrong.

Green Flag #3: Unfamiliar Territory

This may be obvious, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth saying: trying something new stands out. Books can do something new in big ways and small. But this green flag boils down to: unfamiliar territory is an advantage. Whether that is literal by setting a book in a place that’s not been used over and over again, or choosing a subject that’s never been written about before. “Write what you know” may have a kernel of truth, but I would rephrase it as “write what you know that other people haven’t written about tirelessly before.” The thing I realized long after I first read Cobble Hill is that it’s not a “New York novel,” it is a Cobble Hill, Brooklyn novel.

The exception to the rule often has nothing to do with how the rule was established in the first place.

Interesting insights. Would you say a historical novel set around the time of reconstruction with some of the genre trappings of the western might sneak by if contemporary themes are well established too?

This is fantastic stuff and I appreciate you sharing it…thank you.