There is a time reading a manuscript when an editor can become irrationally angry. A writer is going off in the wrong direction or making the same mistake over and over again, and at some point, you’ve had it. The feeling is akin to having a bad argument, where the person on the other end just can’t absorb anything that you’re saying and doesn’t seem to be listening to you at all. Only in this instance the person you’re getting progressively more exasperated with isn’t there, and this person is in fact a stack of paper that won’t change no matter how much you huff and puff. In a weird way, this energy is a galvanizing force, a bubbling sense of righteousness that fuels an editor to hack away, fill the margins with red ink, and get a book back into proper order. Admittedly, this is fairly rare (it never happens with my authors—of course!).

More often than not this kind of anger edit occurs when editing nonfiction rather than fiction. There are a couple of reasons for this. For fiction, editors have often read the entire novel once before they agree to acquire and edit it, as fiction is sold to editors almost always as a completed manuscript. Or, the manuscript comes from an author that the editor has worked with before. Either way, with fiction, an editor generally knows what to expect. Nonfiction is more often sold on outlines and sample chapters, such that when the editor sees the full manuscript for the first time it’s much closer to a real draft (unlike a novel which may have been edited and worked over a dozen times before an editor at a publishing house sees it).

There is also, I believe, a fundamental difference between editing fiction and nonfiction. Editing fiction is like wading into the vast unknown of a dream world—the most important edits are often vague suggestions of a direction with infinite possible solutions (e.g. “this character needs to do more”). Some truths might hold across different novels, but more often than not, every editing truth comes with an “it depends” caveat. Nonfiction editing is more like trench warfare — you often know exactly what the rules of engagement are, but that doesn’t make it any easier to capture a few feet at a time. You are down in the mud and perfect victory is a delusion. Because nonfiction editing gets into the quagmire of minutia more often, this leads to more angry edits — the furious marking to make every sentence crisper, every transition clearer, and all paragraphs forever feeding the thesis. To help those experiencing this condition, I’ve devised a few proprietary editing marks for the frustrated editor that you will not find in the Chicago Manual of Style. These are certainly not meant for the eyes of writers, but can offer some catharsis to the editor toiling away at a Sisyphean task.

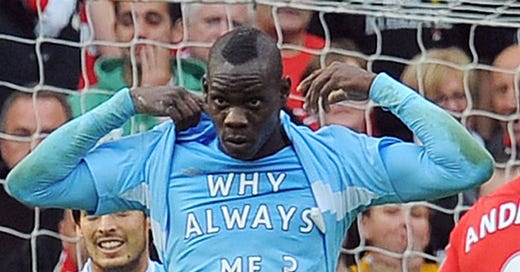

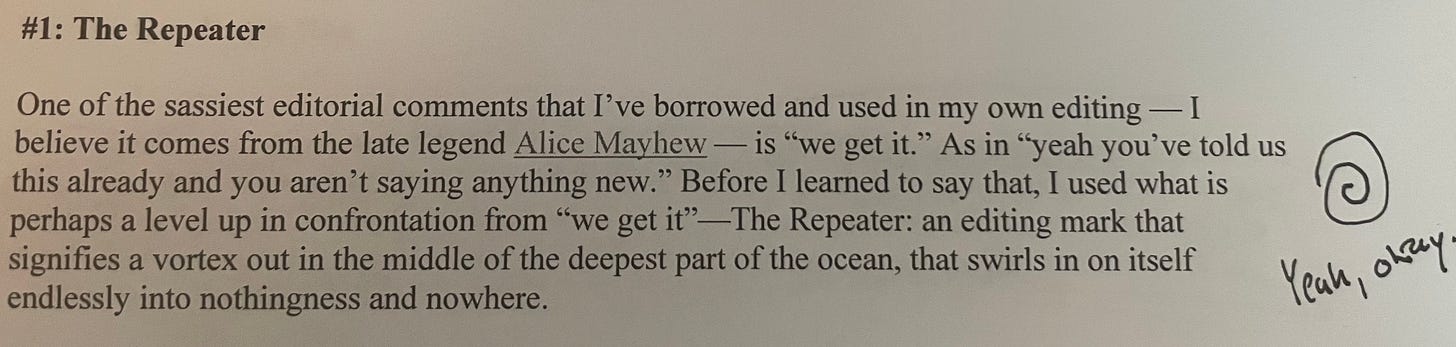

#1: The Repeater

One of the sassiest editorial comments that I’ve borrowed and used in my own editing — I believe it comes from the late legend Alice Mayhew — is “we get it.” As in “yeah you’ve told us this already and you aren’t saying anything new.” Before I learned to say that, I used what is perhaps a level up in confrontation from “we get it”—The Repeater: an editing mark that signifies a vortex out in the middle of the deepest part of the ocean, that swirls in on itself endlessly into nothingness and nowhere.

#2: The Eyes

Controlling an exasperated eye-roll is an important life skill that can save you from getting into a lot of trouble. This is not something you have to worry about when you’re scratching out notes and doodle marks that only you will see. Let the full sigh out, the mouth agape, and the eyes pop with this cartoon eye roll of disbelief. Best used when you cannot believe that a writer took an incredibly lazy shortcut. Although this is #2 on the list, it is only to be broken out truly when you’ve had it.

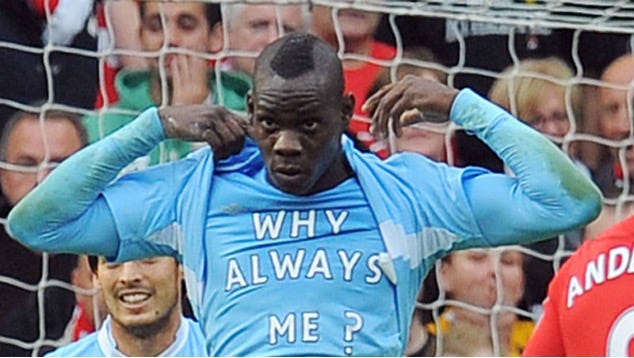

#3: Giant Question Mark

Sometimes a question mark is innocent. A 12-point, even-sized-with-the-text, innocent integration of the slightly confusing. Then the question mark grows, at first not so noticeably, like a high school student increasing their font size by .5 to make the page count. Then it evolves to paragraph size, transforming from a gentle “what?” to a Godzilla-like “what are we even talking about here?” This is a particularly helpful mark when a writer starts to stray from the topic at hand— it’s a book about Lincoln’s first year in the white house and they go off on a two-paragraph history of dog breeds in the United States. A giant question mark is an editor’s cry for help: why always me?

#4: The Quadruple Hex

When all Chicago approved editorial marks fail and so do these extra made-up ones that serve no real constructive purpose, there is only one option left. The angry, irrational quadruple hex—that’s 24 lines if you’re counting—scribble cross out. An enraged cloud that assists the editor in remembering material to suggest cutting, but also helps let that excess buildup of frustration so that they can later write “not necessary” (another Alice Mayhew trademark) politely into the margin of the manuscript they’ll actually send to the writer.

Book Club for May 2024: Real Americans by Rachel Khong

Just a simple reminder to read along if you’re interested. I’ve started and it’s good so far! Full breakdown coming on June 20th.