Great Expectations and an Update on a Very Different Classic

What is the hardest kind of book to write? And our first whale "sighting."

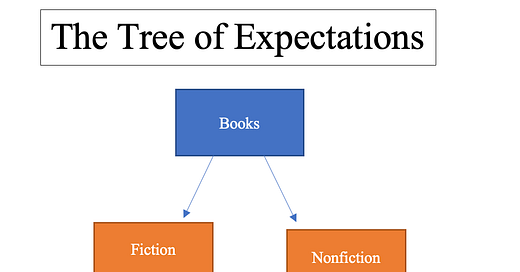

Editor Breakdown: Expectations

In this reoccurring segment we embrace the double meaning

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dear Head of Mine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.