Biggest “News” in Books: The Greatest Books of the 21st Century

The New York Times is currently running a series to pick the best books of the 21st century. Is it a little too early to be tallying the best books of a century when we’re not even a quarter of the way through it? Probably. Super lists like this New York Times list function as a conversation (read: outrage) machine as nothing fires up people like debating the highly subjective “best” of something. I’ve remarked on this before, but look no further than Rolling Stones’ greatest songs of all-time list to see a masterclass in purposeful outrage listing (basically their move is to take an old, iconic, agreed-upon classic song and then rank something much newer and more poppier right above it in an attempt to take years off the lives of Boomers).

PBS did a book super list a couple of years ago that was dubbed “The Great American Read”. This was a straight-up nationwide popularity contest, voted on by the public, and resulted in a young adult and school-oriented list. Sadly, most people stop reading fiction when they grow up, and so it was observed by many that To Kill a Mockingbird often tops these lists because it has been pumped into the American school system by the millions for decades as required reading (and it is also very good and people generally love or like it). Meanwhile, Time just let two guys pick the best 100 novels of all time.

The New York Times has a differing methodology than these lists, polling hundreds of people in the literary world from authors, to major influencers like Sarah Jessica Parker and Jenna Bush Hager, to more authors (503 of them to be exact). What it has produced thus far — The New York Times has only released the first 60* — is an interesting mix of critically popular books. Nearly everything on the list has won one of the major literary awards or was a finalist for one of the major literary wards. Given this certain bland critical predictability, what most interested me were the 18 of 60 books that did not win or nearly win a Booker, National Book Award, Orange, Pulitzer or Nobel:

Literary Luminaries

Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward

On Beauty by Zadie Smith

Pastoralia by George Suanders

Train Dreams by Denis Johnson

Runaway by Alice Munro

Although these specific books didn’t win any major awards, their authors certainly have for others books. They are such giant literary names in general that these titles are hardly a surprise. Jesmyn Ward for example, has two other books on the NYT’s 100 list, both of which won the National Book Award.

Memoirs

The Copenhagen Trilogy by Tove Ditlevsen; translated by Tiina Nunnally and Michael Favala Goldman

Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi

The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson

Nickel and Dimed by Barbara Ehrenreich

Overall, it’s surprising how memoir heavy this New York Times 100 list is so far. We might speculate that this is a factor of time and being only 24 years into the century— great memoir being some of the most emotionally and immediately impactful books while novels tend to endure and be reread over time.

Commercial Successes

The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante

Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

An American Marriage by Tayari Jones

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin

Always an interesting part of critics super lists (unless it is Rolling Stone trolling) is the big commercial selections that have transcended popularity to be embraced by the critical community. Often these are the kind of novels that end up have an enduring power through time.

True Outliers

The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander

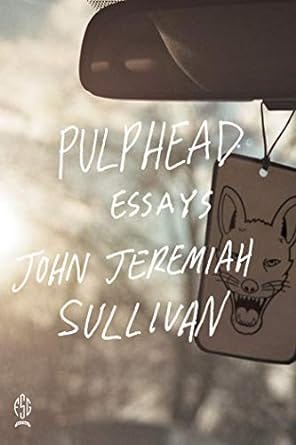

Pulphead by John Jeremiah Sullivan

We the Animals by Justin Torres

The Flamethrowers by Rachel Kushner

10:04 by Ben Lerner

Three novels and two works of nonfiction that didn’t win any awards in their time from authors who are critically loved but not Giants of Literature. These deep cuts are the most interesting, as they have risen to importance in the lives of this highly literary voting body without out-of-the-gate, wide overwhelming critical consensus in their day. The New Jim Crow is the outlier of all outliers, a small academic press book that is the foundation for a huge social, policy, and political shift. Pulphead is a collection of essays I’d never heard or seen before— and my assumption is that it must be pretty great if that’s the case. The three novels are probably that rare species of great book that are highly influential to writers but didn’t have the popularity or scope or import to win the big awards when they were first published. Another instance where it’s safe to assume these novels are special because voters would have to arrive at them without culling from the major awards lists first.

How To Read a Super List

With nearly 2/3rds of the list comprised of major award winners, overall, the first 60 books in The New York Times list gets to the heart of the problem with making any super list about books. A problem that artistic mediums like films or music don’t have, which is that books take a heck of a lot longer to consume. Listening to 300 new songs a year would be mildly annoying, watching 300 new movies pretty difficult, while reading 300 new books requires you to cancel all of your social plans and become a hermit. That means the making of The New York Times list ultimately comes down to a simple calculation of “what has this subset of people actually read?”. Factor in some layer of critical consensus to weed out books that are on the entertainment side of the spectrum and you have a list that looks like this. That’s why it’s important to read these super lists by picking apart their methodology to try and find the interesting or outlier choices, the ones that give you a new, exciting reading list rather than trying to cram down Pulitzer Prize winners like vegetables.

*Editors Note: I wrote this right before The New York Times published 20-40 on the list, but hopefully this is a helpful template to look at the rest of the list as it comes out. The pattern, unsurprisingly continues, as of the next 20 titles only The Last Samurai by Helen Dewitt fits the above criteria of a true outliner (and just barely, it was longlisted for the Orange Prize).