Word count and page count are arbitrary numbers that take on outsized importance for editors. Like the culturally significant numbers 3, 7 or 10 — it’s hard to say where mythology ends and pattern begins. Books with different page lengths start to have personalities. Certain arcs. Like the rhythm of a 2- vs 8-minute song. Even themes and types of books start to coalesce around a certain page length. A generational family novel, for instance, just isn’t told in less than 400 pages (One Hundred Years of Solitude), and the sweet spot for these novels feels like 500-600 pages (East of Eden, White Teeth, Pachinko, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn) or 800 pages (The Brothers Karamazov), but somehow not the no man’s land of 700 pages. If an epic family saga was delivered at 200 pages, there would be plenty of reason for its editor to be concerned.

We’re here to talk about the opposite of long books, of course: cutting. When people think of editors, this is probably the first thing they think the job entails. And it’s not, not true. Editors exist partially to enforce these somewhat arbitrary mythologies and patterns. If I had to pick the quintessential novel length, it would be 320 pages (fun fact: page counts happen in increments of 16, because of the way book printing works). Is this actually an ideal length for a novel? Of course not. It’s like how most viewers feel that 90 minutes (1.5 hours) is the ideal length for a film, yet if you look at people’s favorite films, they usually run 120-150 minutes (2-2.5 hours). My guess is that a chart of my favorite novels might show the same. Yet 320 pages, or the equivalent of a 90-minute film, often it feels like the right amount for the ideal, average book, the amount of pages before bloat can set in if the writing is not in expert hands.

Less isn’t Always Better

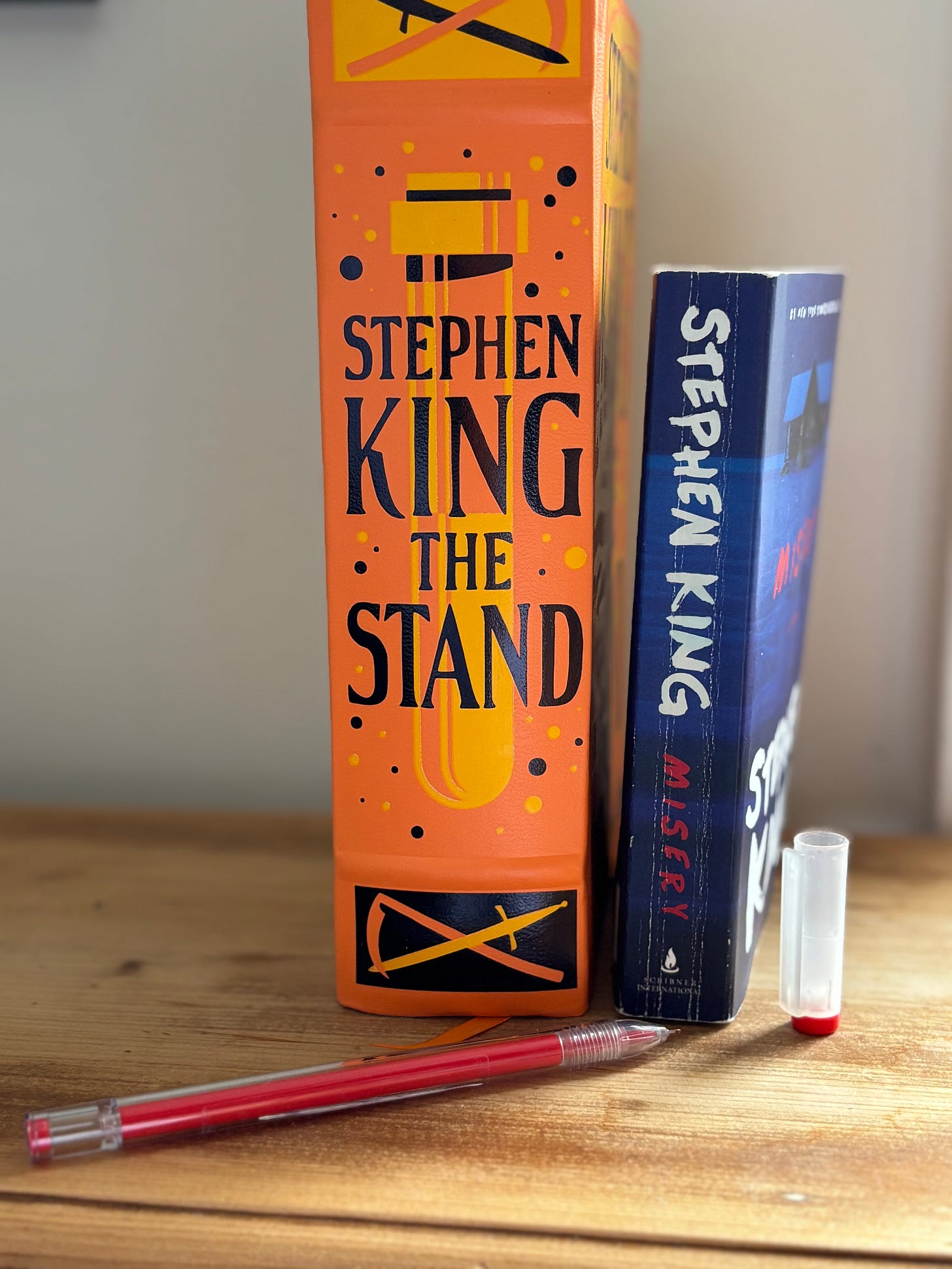

The perfect example of the struggle over length between editor and author is probably Stephen King’s The Stand. As the legend goes, the manuscript King turned in was so long that the printing technology at the time could not accommodate printing the novel in one volume and selling it at a reasonable price. Under the advisement of his editor, King cut down the novel from about 1,200 pages to 800 pages. King didn’t like the idea of this at all, and won out in the end, eventually restoring the 400 pages in the uncut version in the 90s (presumably when technology caught up), which is the edition that is primarily now sold until this day.

Which version of The Stand is better? I don’t have 40 straight hours to read both and come to my own conclusions. But the King predicament shows that strong reasons for cutting can often have nothing to do with quality. King’s publisher and editor decided they could make the great book they had even bigger by selling it in one edition at a lower price point. Many writers looking for publication, or literary agents selling books to editors, will run into trouble selling books that are over the standard lengths for their genre. If you take out 400 pages in cuts and this makes the book 5% worse but increases the likelihood that someone will get to the end by 50%, those cuts are likely worth making. King’s publisher may not have made the right move given 20/20 hindsight, but often getting the right length book can mean winning over many more readers—you want to give a great book the chance to survive and thrive. Cutting isn’t always good, but it is often necessary.

The Essential Rule of Cutting

If you’re trying to make big cuts, whether it is fiction or nonfiction book, long or short, the one essential concept is: cutting means deciding what information you can get rid of.

Put yourself in the shoes of a kidnapper and you have to give the ransom instructions (for some reason cutting a manuscript brings to mind hostage negotiation, couldn’t say why). If you have unlimited time to explain the drop-off instructions, you’d control for every variable so you don’t get caught— how many people should make the drop-off; what kind of car they should drive; steps they should take to prove they aren’t being tracked or followed, etc.. But let’s say you have sixty seconds to give the drop-offs instructions—now you have to pick and choose the most important details. If you know your phone can be tapped in ten seconds, you might just have to say: “drop 10 million under the clock tower at 5 past 3 tomorrow.” In this final instance, you can’t waste time on precautions to forgo the amount, the location, and the time. Editing to length all comes down to how long you have to convey information and therefore how much you have to rely on the reader to fill in the gaps or simply go without.

1. Trimming by a Thousand Cuts

One way to get rid of information is on the micro level. Going sentence by sentence, getting across the same meaning with less words. This is known as line editing.

Here’s the opening sentence of Heart of Darkness with some of these edits:

“This could have occurred

nowhere butonly in England, where men and sea interpenetrate,so to speak-the sea entering into the life of most men, and the men knowing something or everything about the sea, in the way of amusement, of travel, or of bread-winning.”

These aren’t massive changes to the voice or rhythm. A more strident editor might ask the writer to eliminate the repetition of “men” and have Conrad reconsider the extremely vague terms of “something” and “everything.” Actually, the entire phrase “men knowing something or everything” is fairly useless if you spend time considering it. Instead, we’re condensing “nowhere but” to almost a 1:1 swap, “only”, and getting rid of the verbal tick “so to speak” when it is already clear that he means “interpenetrate” as a figure of speech.

But the harsh reality of cutting little by little is that it almost never adds up to much. I’ve poured days into line-editing, hacking and slashing at each sentence, and rarely does it add up to more than a few pages of trimming when all is said and done. This work undoubtably makes a book tighter and stronger, but if too long is the issue, a thousand tiny adjustments is not the way to cut.

2. Stare into the Abyss

Sometimes the best thing an editor can do for themselves and for their writer is just to give them parameters and let them figure it out. This would be something more like the Rick Rubin approach to editing. Rubin is a legendary music producer who has worked with acts as varied as Jay Z, Metallica, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Linkin Park. He’s famous for being a sort of music guru, who gives a small piece of advice, sometimes completely un-music related, which helps the musicians he works with create their masterpiece. He famously once told System of a Down to pick a random book off his shelf and turn to a random page— there they found the exact words they needed to complete the lyric to what would become their most popular song. This might seem silly or apocryphal or like snake oil, if Rubin didn’t have a habit of doing it over and over again, making a tiny suggestion that has a huge impact (“Jay Z, why not go acapella for the first five seconds of 99 Problems?”).

Rubin shows that the correct editorial approach is not always for the editor to step in and try to do the writer’s (or musician’s) job. Cutting is no exception. If a manuscript is delivered way over its intended length, it can be much more beneficial for the editor to say “cut 100 pages and send it back” rather than having both editor and writer tinker away at the margins. Or for the editor to give other helpful, large vague notes like “remove this character”, “start in a different place”, “put the first twist on page 59” and for the writer to figure out the very hard work of doing that without any hand holding.

There are invisible, unfixed lines between the editor and writer, between creativity and mechanics. Often, a diligent and dedicated writer can retain more of the project’s creative core by going off, staring into the abyss by themselves and deciding what matters and what doesn’t. The size of the editorial push can often be inverse to the amount of instruction given.

3. Using Time

The easiest way to eliminate information is to manipulate time. Time is a writer’s friend and perhaps the final stage of mastery. A few weeks ago, I mentioned the way Ann Patchett uses time in her novel Commonwealth. Patchett is telling a rather long story of a family (not quite a saga), but also wanted to hit the perfect novel size (336, close enough). To accomplish this, Patchett hard cuts several years between each couple of chapters, picking up the scene at the next important moment in the overall story. Patchett probably knows what occurs off the page for her characters in these gaps, but a writer looking to make big cuts should look at her choices by way of example. She’s choosing to take out whole years of information.

This works just the same in a work of nonfiction. A few years ago, I read a delightful book Seven Games: A Human History by Oliver Roeder. The title and subtitle tell you all you need to know about the organization of the book. It’s easier for a nonfiction author to cut time if they choose the right framing device. At the end of each chapter, Roeder has given himself permission to restart with a new game and pick up at any point in human history (from imperial Japan, to the early days of IBM, to ancient Egypt, and more). If a historian picks a certain topic, they can fast-forward decades or centuries within a couple of sentences. E.g. “It took thirty years to rebuild and it would be another century and a half before natural disaster stuck once again. This time in the form of…”.

To see this type of time manipulation and cutting of information on a smaller scale, look to crime fiction. In this genre there’s often a need to get every point of view and character up to the same speed, but your reader (and editor) will be somewhat frustrated if you rehash the entire scene they read in dialogue. The solution is to condense this all into something like “She told her partner everything she had learned on her surveillance detail.” A good rule of thumb is that if the reader isn’t going to learn anything new, then it’s a form of redundancy to show it twice. Now if this fictional partner adds a few lies about what she saw on her surveillance detail, that’s another story.

Everyone Can Benefit from the Red Pen

The argument for cutting when something doesn’t work is obvious. But even considering a writer who is very good and knows what they are doing, there’s usually good rationale for cutting a project. It’s the Martin Scorsese Rule. Scorsese is the one of the greatest directors of all time. But his movies have gotten, ahem…really f’ing long. The Irishman and Killers of the Flower Moon are better films than most directors will ever make, but there’s also the lingering sense of any viewer with an editor’s brain that there’s a sharper, shorter version of the film within each film. Cram every sketch and unfinished piece that da Vinci did into one room and you might not be able to focus on the achievement of the Last Supper. Even a lot of good stuff can overcrowd the transcendent aspects of a piece of art.

To give two extreme book examples, some of the most common criticisms of the ultra-long novels Moby Dick and War and Peace is that the former has too much talk of whaling and that the war parts in the latter are actually quite boring. So, while we’re very glad that these novels weren’t cut and clearly their length didn’t hamper them from becoming literary classics, an editor is left to wonder if you cut the whale parts and the war parts if these novels would have been literary staples, like fellow 1800s adventure novel Treasure Island or Tolstoy’s more widely-read classic Anna Karenina, rather than daunting classics that often languish on reader’s bucket lists.

No matter how good the writer, there is always cuts that can be made. And no matter how great the book, there’s always a new form of a book that editing (in the form of cutting) can unlock.

One of the greatest pieces of editingI ever got was an editor sending me a short story to read because it had the same elements the feature I was writing had (including voice, structure, pacing) and it unlocked so much for me. We line edited after I made some major changes.