When’s the last time you looked up the actual definition of a word? As an editor I do this all of the time, mostly out of the desire not to embarrass myself in emails. It can be easy to believe you know the general meaning of a word until you actually need the precision of saying exactly what you mean.

A result of wondering “what word am I actually using here?” came when questioning the publishing term “midlist” (as in the middle of a sales chart). In my head, “midlist” had a logical association with “middle” or “mid”, meaning mediocre or just okay (or low quality—in the spirit of this newsletter, I looked “mid” as a slang term up). I’ve been reading and ranking every Haruki Murakami book and I completely misused the term “midlist” as being interchangeable with “middling” when I examined and ranked the middle of his catalog.

The real definition of the publishing term midlist is actually quite different and interesting. Wikipedia defines it as: “a term in the publishing industry which refers to books which are not bestsellers but are strong enough to economically justify their publication (and likely, further purchases of future books from the same author).”

This is really striking. Despite the “mid” association, “midlist” has nothing to do with the quality of the books. In fact, at least according to Wikipedia, it’s almost the complete opposite. Midlist connotes that a writer can justifiably keep writing and publishing books because enough people are buying and reading their books. That’s a beautiful, symbiotic thing. It’s an impressive designation despite its misleading name, maybe even more impressive than “bestseller.”

There is a class of bestsellers that publishers pay millions of dollars for that get on to the New York Times list for a week or even two and end up losing tons of money. Is this more successful than any “midlist” book by Wikipedia’s definition just because it’s technically higher on the sales charts? Absolutely not, and yet that author (and editor, and publisher) get to say they made a bestseller for life. No one besides industry insiders, and not even the majority of them as time passes, will know that these bestsellers weren’t business successes.

Meanwhile the midlist gets no love. You can’t find what’s on the midlist by opening to the New York Times bestseller lists. Amazon won’t as readily show you the 400th-600th bestselling newly published books on their live sales rankings. While the midlist might not be the bedrock of profitability for publishers (that does come from the blockbuster bestsellers), it’s the lifeblood of a culture of reading and literature, where writers get a decent wage, a fair number of people engage with their work, and they get the chance to get the next publishing deal to write the next book.

My first ever book as an editor Girls Can Kiss Now by Jill Gutowitz was a success of the kind I’m talking about, one that appeared on a regional Indie bestseller list its first week of publication, but more importantly kept selling steadily, most likely because of reader recommendations (after an initial wave of good press), and found an audience. It was fulfilling in a way that’s more important than bestsellerdom and the reason many of us join the book publishing business — getting really good books that we love to a significant number of readers. Enough that someone else who wants to write something like a queer memoir in essays through the lens of pop culture can point to Gutowitz’s success and say “hey, people want this” and a publisher might pay them to do it (see: comps) or that the talented Gutowitz can write and publish another book if she chooses.

The midlist, for many reasons, is where it’s at. But what exactly is it?

What is a “Midlist Book”?

We know what a bestseller is because there are copious lists to catalog them. Also, even if the answer is more complicated if you search for the actual definition, “New York Times bestseller” — the books that sell the best— is an entirely intuitive concept as a methodology.

Midlist books, or books that are able to “economically justify their publication” is a bit trickier of a concept, to put it mildly. No one besides the publishers or the individual authors, who know the advance (the money paid upfront to authors to write the book) they received and how many copies they’ve sold, can know the real answer to what constitutes “the midlist.” Because while sales are reported, the definition of “economically justifiable” requires you to know how much the publisher invested in the book (how much they paid the author; how much it costs in labor and printing to make it; how much they paid to advertise and publicize it). These costs are closely held business-sensitive information. And by an ungenerous definition, “the midlist” could include all the books that are self-published, since the cost to produce those is theoretically close to zero (but let’s stick to “traditional” commercial publishing and not go down that rabbit hole).

To come up with examples of midlist books, we have to use our common sense, some hard data, and a little insider intuition. The platonic ideal of a midlist book that comes to mind for me is We Ride Upon Sticks by Quan Barry. Barry is not a household name, but a poet with a lot of credentials. I feel safe in saying that without a massive sales track record or a highly commercial elevator pitch that Barry’s publisher didn’t pay her an exorbitant amount for We Ride Upon Sticks. According to LitHub’s bookmarks both NPR and The New York Review of Books gave the novel mixed reviews.

We Ride Upon Sticks is a book I had nothing to do with professionally but find myself recommending constantly. It is a novel that is like if the show Yellowjackets was a comedy/coming-of-age story instead of a horror/thriller. I mentioned it a few weeks ago when writing about sports novels,

“[The novel] centers around a group of once-losing field hockey girls who perform a satanic ritual involving Emilio Estevez in order to gain the dark power they need to win. This novel is so damn enjoyable from page to page that you’ll completely forget why the sports part even matters. What you’ll be left with is the hilarious moments of bonding in ways that don’t exist outside of growing up or the context of being on a team together.”

By sheer reader word of mouth, it seems (mine included), We Ride Upon Sticks ended up selling 10,307 hardcover copies (around 40,000-50,000 copies total when all was said in done – paperbacks, eBooks, audiobooks). With these sales it is exceedingly safe to assume that the novel made good money for the publisher and that this helped Barry to make deals to write more books (she has since published one novel and made a deal for her next).

A hugely successful publication, We Ride Upon Sticks was the #405 bestselling fiction hardcover published in 2020. It’s worth noting that this puts We Ride Upon Sticks in the top 1% of bestselling fiction hardcovers for books published that year— yeah, even making “the midlist” is extremely hard in book publishing (which is why it should be celebrated). We Ride Upon Sticks never even grazed the bestseller list. For context, many weeks this year it took selling 8,000-10,000 hardcover copies in a single week to get on the bottom of the New York Times hardcover fiction bestseller list.

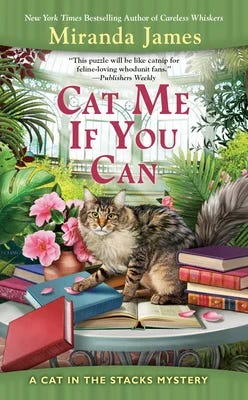

So as we look to define “the midlist” and then see what’s currently on it for this last year, we’re going to honor of We Ride Upon Sticks and set the big publisher “midlist” threshold around 10,000 copies. Really, having a good knowledge of the economics at play, the floor of the midlist is probably a little lower than this, say 5,000 hardcover copies*. In 2020, that would make the official bottom of the midlist cutoff Cat Me If You Can (wonderful title) by Miranda James.

When does a midlist book become a bestseller? Where is the upper limit? Looking at fiction the same year as We Ride Upon Sticks was published, New York Times bestsellers seem to reliably hit around 30,000 hardcover copies sold (the bestseller list is a weekly list that’s incredibly fickle, so this is highly imperfect). Hardcovers that crossed the 30,000-hardcover mark and hit the bestseller list include books like James Lee Burke’s 40th book and 23rd Dave Robicheaux novel and the adult debut, Chosen Ones, by Veronica Roth, the author of the popular young adult Divergent series.

What’s on The Midlist!?

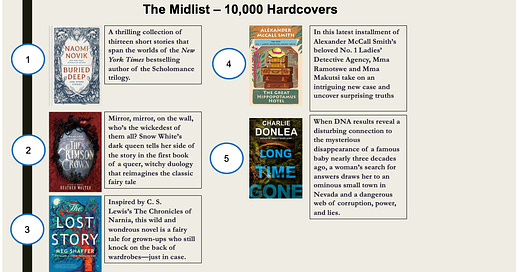

Like the New York Times puts together their bestseller list, I decided to make my own list that is a snapshot of this concept of the midlist in order to celebrate these unsung heroes. The books passing the reasonably economically viable (are you catching on to why this hasn’t caught on?) milestones of 5,000 and 10,000 hardcover copies sold.

To compile The Midlist, I looked at fiction books** published in 2024 that have just recently crossed these significant marks. These books are probably not ones the average reader has heard of, as publishing tends to seemingly coalesce around 5-10 mega bestsellers every year, especially in fiction (books that are on the hardcover bestseller list for 20, 40, and even 80+ weeks).

Remember that every bestseller list is editorial (meaning none of this is done purely by the numbers) and so is this list that I just invented. On The Midlist, I’ve excluded some deluxe editions and reissues. But just know in your head and heart that these midlisters below are also in the excellent company of Ann Patchett (Bel Canto Annotated Edition), J. R. R. Tolkien, Louisa May Alcott, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky (White Nights).

2—The Crimson Crown by Cinda Williams Chima

3—The Lost Story by Meg Shaffer

4—The Great Hippopotamus Hotel by Alexander McCall Smith

5—Long Time Gone by Charlie Donlea

1—American Rapture by Cj Leede

3—Glorious Exploits by Ferdia Lennon

5—All This & More by Peng Shepherd

The Midlist is unsurprisingly populated by mid-career authors with lots of previous commercial and critical success. They built readerships over time with help from reviewers, readers, other authors, and booksellers. The list includes more literary and genre bending authors like Helen Philips and Peng Shepherd, as well as steady genre writers like Charlie Donlea (thriller) and Cinda Williams Chima (Romantasy).

There are also a few highly respected, bestselling authors who you might recognize that have slipped into the midlist for various reasons: Naomi Novik writing a collection of short stories; Alexander McCall Smith on the 25th book in a series; Meg Shaffer taking a small step back after a blistering debut.

And finally, one debut, Glorious Exploits— a send-up of Ancient Greece written in a contemporary Irish style (sounds weird and good!).

The point of this exercise is to show that the midlist often has more variety and interesting stuff than the bestseller list does. The midlist is not only where some very good, reliable authors live like Dostoyevsky (okay, his reissues, technically), but a place where the next huge bestsellers often come from. Gillian Flynn was midlist before Gone Girl, Taylor Jenkins Reid was a midlist author before The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo (in fact, this novel would have fit the definition of midlist in its early years of hardcover publication—the novel in total has now sold over 5 million copies). Alison Espach’s The Wedding People just celebrated its 19th week on the New York Times bestseller list, and has sold a quarter of a million hardcovers — all of Espach’s previous books? You guessed it: midlist.

One thing we can all do is learn the definition and do better at talking, reading, and recommending books that aren’t at the very tippity top of sales lists, start with We Ride Upon Sticks or pick something else off The Midlist.

ICYMI: There was an issue with Substack last week and Daunting Classic Part I: A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin was never emailed out, but you can find it: here hosted on dearheadofmine.substack.com.

Daunting Classic Tracker: The Book of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin | Page 166/992 (The Tombs of Atuan)

*If you’re wondering why I keep referring to hardcover copies throughout this newsletter, it is to keep things simple and compare apples to apples. Generally (but not always) one can extrapolate a book’s total sales (i.e. sales of paperbacks, eBooks, audiobooks) from hardcover sales.

**If you’re wondering why we aren’t doing a Midlist for nonfiction, it’s because the “how much did a publisher pay” side of the equation is almost impossible to determine and even more difficult for nonfiction. There is a higher floor and more volatility for how much a big publisher typically pays for nonfiction, so there there are a lot of nonfiction books that I would venture to say sell 5,000 and 10,000 copies and lose a boatload of money for their publishers.

I've read both Hum and Glorious Exploits. They fall into the category of "books that make NPR's (or other large publication's) long list of staff picks for 2024."

These are both books that are high quality, but that aren't "prestigious" enough to make lists for the major awards. They might make lists or win lower-level awards (Glorious Exploits won the Waterstones Debut Fiction Prize 2024 and the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize for Comic Fiction, two awards I hadn't heard of before), and they'll probably garner a few reviews in papers like the NYT or sites like The Guardian.

Just wanted to add some info on the two I've read! I agree that they're the lifeblood of "reading culture." They're the sorts of books that avid readers love, because hundreds of them come out every year that meet a baseline level of "quality." You can *always* find a book of this type that you'll enjoy.

Such great insight. Thank you for this!