April Fools might be our strangest “holiday” if you step back to think about it. It’s the only widely recognized “day” I can think of that asks people to be funny. Luckily the prompt for April Fools’ Day is pretty basic — just lie about stuff — so there are some helpful guardrails for would-be comedians. Most people have a decent sense of humor, but as anyone who has witnessed a disastrous best man speech where they try to wing it knows, when a regular person tries to be funny on command it rarely goes well. A disastrous best man speech is the perfect analogy for humor in literature. If tasked to devise one rule for being funny in books it would be…

Don’t Try to be Funny

This is the sum total of my observations on humor in most books: it works best, foremost, when the writer isn’t trying to make you laugh. There’s something about the flattening of words on a page that makes forced humor particularly ineffective. When the author is trying to create an absurd situation or throw in lots of exclamation marks for a punchline, it is off-putting rather than funny. These showy acts of humor (loudness, hand gestures) in social situations indicate unseriousness and signal listeners to laugh along—and even if it’s just to placate the person, we often do. Humor on the page works in almost the opposite way.

Dry humor works better in writing and in fiction than it does in person. Laughs that don’t foist themselves on the reader but let them get in on the joke. It is no mistake that dry humor in person often works when there’s some intimacy between the people, some sort of intellectual understanding that what’s being said is with a wink or a subtle smirk (think Bill Murray in Lost in Translation). Best of all, in writing this works when done with complete sincerity, almost as if the person doesn’t know what they’ve said is funny. Here’s such a paragraph from Danzy Senna’s Colored Television:

The Millennials threats, Jane had learned, were to be taken seriously, whereas the Gen Zers you could ignore, ride it out. They were sleepier, more half-hearted in their outrage. Last year, when a white professor had stood in front of his class giving a lecture on the history of stand-up comedy and, trying to quote Richard Pryor, used the N-word in its full, uncut glory, three undergraduates had stormed out of the classroom and walked directly to the administration building to report him. It had seemed the professor was doomed in the moment, but the aggrieved trio apparently became overwhelmed by the paperwork required to file an official complaint, and after a few days, they settled for creating an Instagram page where they detailed their slights in blurb-size anonymous posts.

The Flatness of the Page

The difference between literature and on-screen or even audio comedy is that on the page there is no ability to sell a joke with a gesture or sound. It’s no more evident what a disadvantage the writer is at than when watching a truly great stand-up performer. When a comedian like Chris Rock is cooking with excellent material, he’s an all-time great. But further evidence of his greatness is that he can make material that’s subpar (for him) work with rhythm and intonation. Steve Carell’s infamous Chris Rock impression in The Office at its most basic level, is about how racist and cringey a white person reciting Chris Rock standup is, but secondarily, more subtlety, it is a joke about how normal people couldn’t replicate comedians even if they were handed the material.

Recently watching Adam Sandler’s latest Netflix stand-up special Love You, you can see this in full effect as well. Sandler’s brand of comedy, it’s fair to say, isn’t highbrow. But the well-trod ground of family and marriage material can be changed and elevated by performance. Even his simple observational humor (“old guy with a kid”) is much better with a killer baseline. His haunted everyday occurrences call and response song is also worth sticking around for.

This is also why audiobooks—although there is a constant silly debate on social media to this fact—are quite obviously a different medium from print books (solving online debate #2: you didn’t “read” an audiobook, you listened to it). Listening to Ali Wong’s memoir Dear Girls was a delight, but I have a sneaking suspicion that all of the jokes wouldn’t have hit as well without her line readings. Like any great comedian/performer, she’s elevating the material that the flat page might be more unforgiving to. On the audiobook, she can sell lines that aren’t quite as good without her voice such as:

[Tips on Giving Birth] 11) Require all visitors to bring food from your favorite places that don’t deliver. Eat sushi and deli meat, you deserve it after having been deprived of it for so long. Hell, eat food out of the trash if you want, you are finally free to get an out-of-control listeria infection.

Comedians Are the Exception

Duh…Speaking of comedians, they are often the exception to the rule that writers trying to be funny aren’t funny. They are professionally funny. And while performance is a huge aspect of stand-up, for most comedians’ jokes start on paper. They’re writers to start with. I’d say that this makes memoirs by comedians, of any category of celebrity memoir, the most reliably good.

From The Daily Show, both Trevor Noah and Michael Kosta have written enormously funny memoirs. Amy Poehler and Tina Fey are two of the O.G. comedian memoirs from the early 2010s that arguably kicked this renaissance off and still hold up. But even though all of these memoirs contain more straightforward, identifiable joke jokes, stand-up comedians also tend to be astute storytellers. They are keen observers of form and timing, and often are clever enough to adopt the straightforward style of a good novelist. Here’s a passage from Noah’s Born a Crime:

There’s a comedian’s embellishment here and there (it’s doubtful Noah remembered word for word what he said at nine), but for the most part he’s letting the absurdity of the situation speak for itself without breaking the fourth wall.

Three Recommendations

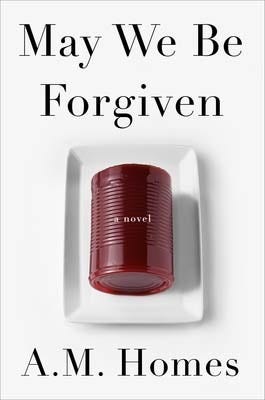

1. May We Be Forgiven by A.M. Homes

When I first read this novel back around 2015, well before I knew a thing about book publishing, it was a revelation. In fact, it probably accounts for a decent part of the reason I wanted to work with authors and books. A.M. Homes’ suburban fascinations might read like a bygone era to the modern reader (oh, how we might trade our lot for that beautiful 90s malaise now). But May We Be Forgiven is a sweet — as in awesome — and wickedly funny subversion of the dramatic family novel that a lot of men had been writing for decades before Homes upended it (this genre seems to have died soon after Homes’ novel—a coincidence?). One look at the mildly upsetting original hardcover jacket (it starts with a Thanksgiving meal) and you’ll get the exact tone of this novel:

2. No One Belongs Here More Than You by Miranda July

Many more readers probably learned about Miranda July this past year thanks to her smash hit novel All Fours. But her first published book, No One Belongs Here More Than You, is a collection of stories well worth checking out. Want a two-page story that shows mastery of this “letting the reader figure it out” style of humor that works most reliably on the page? Just read “The Swim Team”, first published in Harper’s Magazine.

3. Kevin Wilson’s The Family Fang

Wilson is one of the greats at the deadpan, straightforward method of prose humor, it’s why he can make a story about children who spontaneously combust into flames into a highly accessible and popular novel. In the wrong hands, The Family Fang, a novel about a family of performance artists, could be so cringey, pretentious, and try-hard, but Wilson knows how to come up with something absurd and just let it happen without wiz bang-ing the reader to death. The family takes their work completely seriously. The result is very, very funny (and insightful).

Wilson’s novels inspired me to leave you with this final axiom: when it comes to humor in writing, tell it, don’t sell it.

Just read Swim Team. That is perfection!