Sometimes you pick up a book because it was recommended to you. Sometimes because the cover is appealing. Sometimes you’ve followed an author for years and preorder as soon as it’s available. But in the case of Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Cost of the Perfect Playlist by Liz Pelly, I picked up the book with a hyper specific and personal question in mind: Why is Spotify forcing me to listen to Sabrina Carpenter’s “Espresso”?

If you haven’t heard “Espresso”— it’s fine, it’s fun, it’s silly (the chorus features the lines “Say you can't sleep, baby, I know//that’s that me espresso”), and catchy. A cool pop ear worm. If the song comes on at someone’s house or while I’m in a store, I’m not mad at it. But “Espresso” is not a song I ever went out of my way to put on, it didn’t inspire me to fire up Carpenter’s new album, or go see her on tour. And yet, in the summer of 2024 my Spotify felt engulfed by “Espresso.” Every time I left the confines of streaming the same 9 to 12 Hozier songs (as Spotify informed me at the end of the year was indeed the bulk of my listening) or was looking for new music, “Espresso” was there. Every time I reached the end of a playlist, whether it was sad singer songwriter, hip hop, or (more understandably) Taylor Swift, Sabrina Carpenter was the first auto-played song waiting for me like a villain in a horror film hiding behind the door.

Then I would go to YouTube and Carpenter would be there too: clips of concerts (such that I learned about her nonsense outro gimmick); behind the scenes clips (like when she runs into an older woman in New York who doesn’t know who she is); and of course her own video shorts using “Espresso” as the soundtrack. Without ever searching for Carpenter or the song directly, by the end of the summer I unwittingly became a cursory expert on the rising pop star’s fandom.

But why?

Part of me knows the answer to why “Espresso” became “my” song of the summer intuitively without really knowing the detailed answer as to why. Spotify and YouTube feeding me a steady diet of “Espresso” is part of the new passive, algorithmic, hyper-charged-dopamine-pumping experience of how culture is now consumed. We can’t see these mysterious levers being pulled for us, but we have never been more aware that we’re being manipulated by technology than we are now.

With TikTok’s rise and its business model proving more addictive and effective than other platforms—feeding consumers content based on their habits (addictions) rather than their desires (searches)—every big distributor of art, culture, or social information has followed. Such that even if you’ve never been on TikTok — I haven’t — you feel TikTok’s algorithmic effect across your consumption whether you’ve opted in or not. More and more you’ll hear people say that technology platforms are “giving them” X, Y, or Z rather than they are “seeing” or “finding” X, Y, or Z. The answer to my question about Carpenter, at its simplest, is that by not turning off “Espresso” when it came on —when it was “given” to me — I was subsequently algorithmically bombarded with “Espresso.”

Mood Machine (disclaimer: I work down the hall from the person who published and edited this book, but have not talked to them about it and all these opinions are my own) lifts the veil on this intuitive feeling that we often have of being manipulated like penned cattle. It’s a feeling that most of us consistently ignore as we use these exceptionally cheap platforms (Spotify costs $3.33 a month per person if you have a family plan) to access art or information. Spotify is a great case study because for all of its technological complexity, we can still wrap our arms around and examine it. Unlike TikTok or YouTube or Facebook where trends change by the minute, we at least know what product Spotify is serving: music.

The first half of Mood Machine expertly lays out how this new passively driven “feeding” of content works through Spotify’s recommendation and playlist system. This is what the title of the book references, and it lays out Spotify’s relatively new business strategy of hooking listeners based on moods and feelings rather than artists or genres. This means categorizing music as playlists with names like “chill folk” (there are thousands of variations of “chill”) or “witchy” or “morning coffee” instead of things like “American folk revival” or “witch house” (a real genre apparently) or…there’s no real genre analogy to “morning coffee”, which is kind of the point.

The rub is that Spotify’s algorithm-generated playlists are often a bait and switch. First, they serve songs you already like back to you (my “witchy” and “morning coffee” both lead off with Hozier in the first five songs) and a few really well-known artists. But the playlist is then predicated on alike sounds and the idea behind Spotify’s model is that you’ll passively listen as they calibrate what you don’t turn off or skip in the background. The final step is that Spotify feeds you songs that Spotify pays lower royalties on, meaning they pay artists less and pocket more of your monthly fee. Where does the cheaper music they sneak to you when you aren’t paying attention or using Spotify as background noise come from? It’s made using gig-economy-style hired musicians and AI.

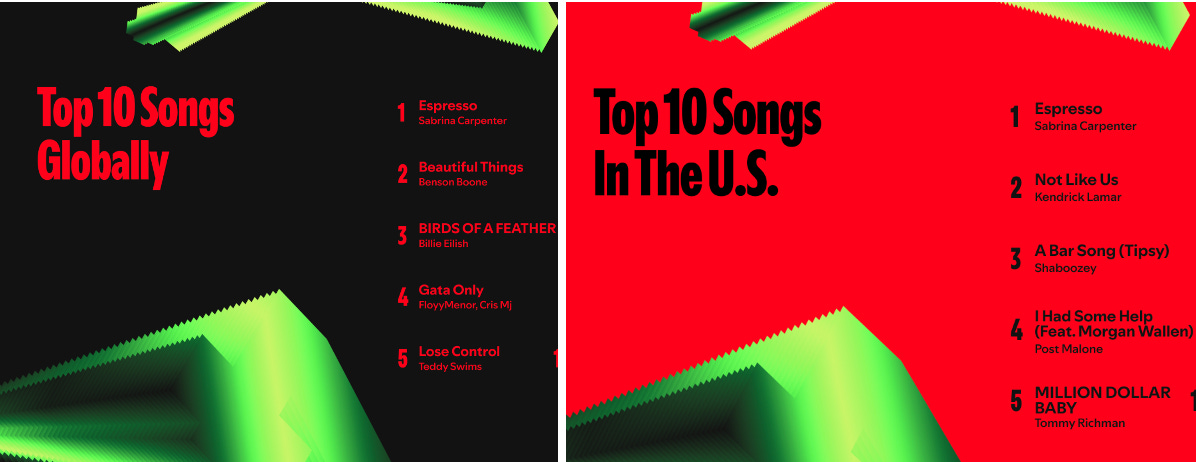

The result is that Spotify is squeezing out what in publishing we’d call “the midlist”— prioritizing everything crappy and cheap as well as everything that’s too big to fail. That’s the focus of the second half of Mood Machine and where Sabrina Carpenter’s “Espresso” comes back into the picture. If you’ve read this far, you’ll be unsurprised to hear that “Espresso” was the #1 streamed song on Spotify in the US and throughout the world in 2024. The major music labels, which are the other dominate driving force in Spotify’s decision making, saw the natural popularity of “Espresso” and used their corporate muscle to jet-fuel inject it into our feeds and ears.

Carpenter is part of the biggest music label in the world, Universal Music Group. Although Mood Machine did not offer specifics of the pushing of this specific song, examining all the mechanisms it’s clear that with Spotify and YouTube and others, the powers that be put their finger on the scale, making sure this hit would be a megahit we couldn’t escape. The scariest part might be that it completely worked. This dynamic is also why “the next big thing” or even “the biggest song of the summer” feels much more hollow than it did 20 or 30 years ago (shoutout to Titanic and “My Heart Will Go On” - 156 million views on YouTube 20+ years after release, now that’s a hit!). Another pop star who skyrocket to stardom last year Chappell Roan, consumed my feeds and yet I talked to a friend my age who had no idea who she was even though they had listened to one of her songs and loved it. That person just wasn’t on the same pop culture centric feeds that made Roan feel like the biggest thing happening. Much of the popularity in both cases might be genuine but the amplification is anything but.

What is happening at Spotify is a microcosm of what is happening in every other form of entertainment. The blockbusters are, relatively, bigger than ever (boosted to made feel us like they’re the only movies…books…articles available) and garbage content is being used at the other end to squeeze everyone else. Spotify exemplifies what the writer’s guild was onto early: AI is not really being used to replace the quality of what artists make but pumping out schlocky facsimiles that can replace their rights of ownership by using cheaper labor (machines recycling bits of existing material). The revelation of reading Mood Machine is the exact mechanics by which this is happening aren’t passive systems at all, but being pushed aggressively to an audience that is constantly being conditioned to receive what comes to them without complaint.

The Word “Vibes” Should Go Away

This is an unpopular opinion I’ve been floating in my personal life for some time, but Mood Machine helped me finally clarify what has intuitively bothered me about the recent vibe-ification of our language.

My issue is that “vibes” are passive, vague, and somewhat meaningless. The ubiquitous use of this term is the social outgrowth of what is happening online and with these platforms like Spotify. To say you do or don’t like “the vibes” of something is to siphon all real agency of your taste into the general bucket of “generally good” and “generally bad.” It is the antithesis of taking art seriously. Judging art on its vibes — those initial impressions and feelings you get when you first encounter a piece of art— reduces music, books, television to the same little pleasure-point nodes as a ten second video clip.

The most powerful action you can take as an individual is simply not use the algorithm when possible (i.e. search don’t scroll) and make sure people you know are informed about what they are opting into (although don’t be disappointed when you get some answer that is a variation of “but I like my cage”). I’ve probably listened to Spotify playlists before or used their recommendation system — another symptom of this system is that you barely can remember what you’ve listened to, watched or done, but that’s a topic for another newsletter. After reading Mood Machine, I won’t. Simply turning off these systems or defying them is crucial. Beyond that it’s an important reminder to not just “vibe check” what you’re listening to, reading, or watching. Choose what you consume with purpose, pay attention to it, debate it openly, and find deeper enjoyment in supporting art and artists than a quick dopamine hit (seek out musicians outside of Spotify’s walls, order a book that’s not on the bestseller list or Amazon carousel wheel!).