You Don’t Really Want Gatekeepers

Discourse vs. Criticism, and Substack

The tension between discourse and criticism has never been more palpable. Substack (where you may in fact be reading this) is a large “platform” for newsletters or, as they used to be called, blogs, that is conflicted between these two modes. Substack has likely been successful because it has a large number of people spend time researching and writing thoughtful essays and articles (criticism and journalism). This is the type of “content” that has become increasingly difficult to find elsewhere on profit-squeezed media websites and in the sea of social media hot takes and video slop. At its best, on Substack readers are able to discover great writers much more quickly and have access to far more writing than what is mediated by traditional media or book publishing (and content like short fiction that has slowly been squeezed out of traditional publishing over time). It’s a gift to get pure gold straight from writers as widely varied and genius as Shea Serrano, Chuck Palahniuk, Miranda July whenever they feel like sharing a thought.

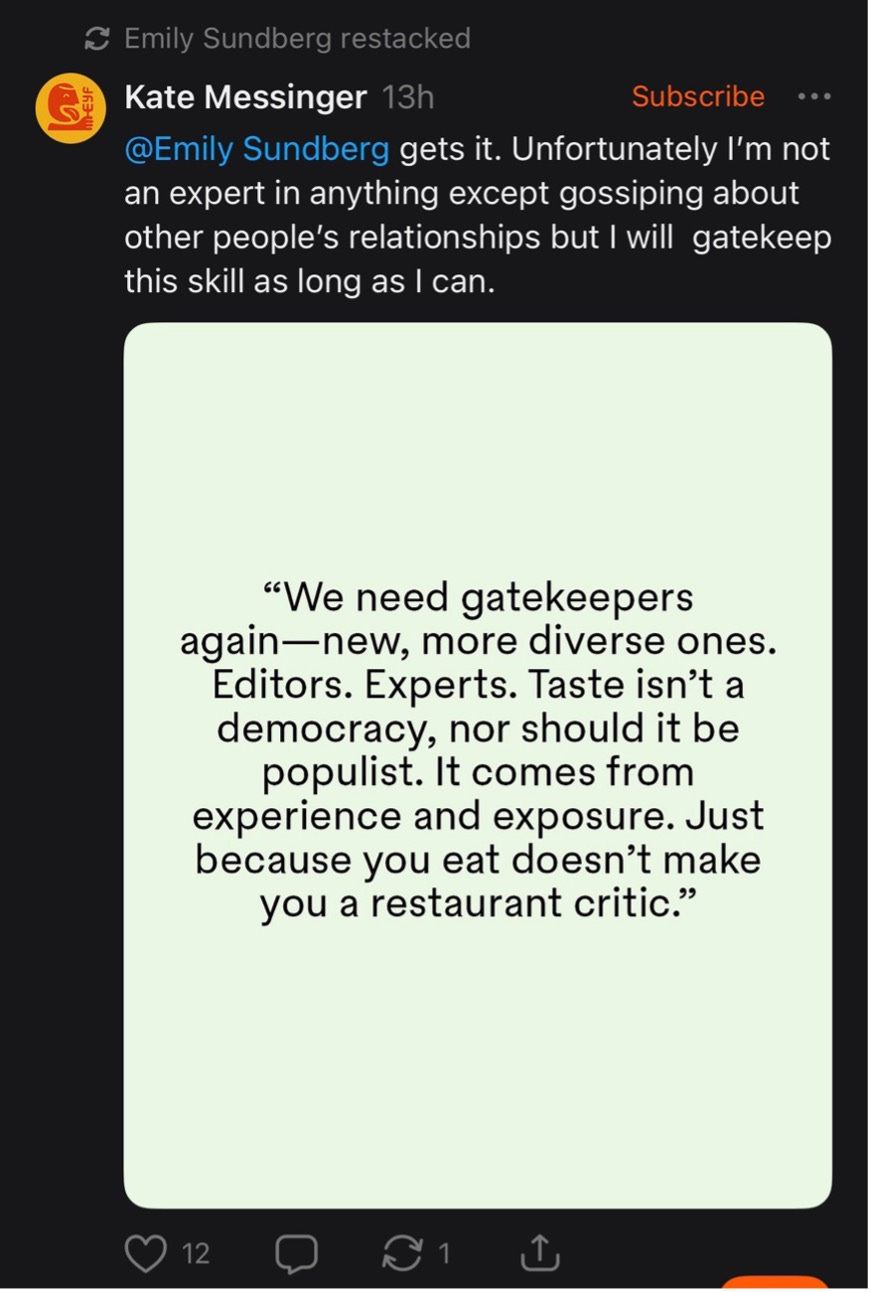

Yet, the age of discourse creeps in, as Substack’s Notes feature makes the platform look a lot more like Twitter or other social media interfaces, encouraging “engagement” and distracting from actually finding new things to read. Mostly, I find that this Notes feed is filled with misattributed quotes to famous writers and some version of the same “me writing to my one follower” type of jokes that bafflingly seem to get a lot of traffic (although maybe that’s over by the time you read this). Although Dear Head of Mine aims for the actual substance, sometimes we all fall into the trap of discourse: seeing an opinion and having a visceral response to it. Such is the case with this quote that made the rounds (on my feed at least) with a lot of readers applauding the sentiment from business and culture writer Emily Sundberg, author of Feed Me newsletter:

As an editor, a profession which Sundberg mentions, and one which many associate with the “gatekeeper” moniker, this quote made me think. No doubt this was just a pithy way to describe real concerns regarding underlying issues about the state of art and its distribution that resonate with many of us. It is also a statement that bristles. Gatekeepers may be a fact of life but they are not something to strive for. At worst the designation of gatekeeper implies a strict control of supply, an ability for a handful of individuals to monitor, restrict, and horde culture based on idiosyncratic taste and access to capital.

In Sundberg’s quote there is a nostalgia for a old world of gatekeepers that no longer exists. Book publishing editors, for instance, control the supply of books that get to market more loosely than ever in history. There is self-publishing for one and there is also more direct market dictates (like social media followings) that are harder for “gatekeepers” to ignore in favor of their taste. It isn’t necessarily the gatekeepers of yore that made the previous era of art distribution better. While there are good gatekeepers and bad ones, it’s merely a different flawed system for getting art out into the world and “new, more diverse” gatekeepers won’t change that. Yet within this simple statement about the want for gatekeepers is a yearning for solutions to real problems. I’m here to boldly claim, as a “gatekeeper” myself, that you don’t really want gatekeepers…

You Want Curators

What the world is increasingly clamoring for is the filters we used to take for granted. The Millennial generation in particular has the benefit of straddling both sides of the technology chasm during their formative and early adult years—they remember Blockbuster, Borders, and the iTunes music store. These were helpful containers that gave consumers a lot of choices (like more than the three TV channels that Boomers grew up with), but still a fundamentally limited option of entertainment from which to choose.

Were these corporate entities perfect? No. It’s why indie movie scenes, indie book publishers, and mixtapes emerged during the same time to bring good, overlooked art to people. But even with their obvious gaps, these pre-internet retailers provided some level of quality assurance. You weren’t at risk of going into a Blockbuster and renting some thrown together DIY film or stumbling upon an unedited, computer-assisted mess of a novel at Borders.

What we want is less choice. And we’d like a system of filtering art that is less engagement-based and more human and thoughtful. It’s why when readers are looking for a new book, they should still probably visit a bookstore despite the higher prices— you have a much better chance of getting something of high quality, based on staff recommendations, and that’s usually worth it. Intermediaries like independent booksellers and book clubs are essential curators.

What’s the difference between a gatekeeper and a curator? A gatekeeper arguably has more stake in the creative process, and although book editors and publishers act as fairly effective quality assurance, a great curator in this day and age is more important than a gatekeeper in filtering out the noise. Gatekeepers help decide what gets made, curators help decide what’s available and how to actually direct people to it. Even if gatekeepers do a good job of weeding out the truly terrible stuff (and we do), curators are the real missing piece, narrowing down your choices and fighting against slop.

You Want More People with Taste

When Sundberg cries out for more gatekeepers, what I think she is really bemoaning, like many of us do, is the fact that many consumers seem to care less and less about the quality of what they consume. If everyone in your town wants to eat junk food, then your supermarket is going to be filled with junk food. Gatekeepers often have little power to turn the tide of demand in the modern age, especially when there are so many ways to get around them.

If people desperately want to read Harry Potter fanfiction and only Harry Potter fanfiction, we can be glad they’re reading and buying books at all, while wishing — often fruitlessly — that they may one day be converted to reading more complex and emotionally rewarding literature. It’s also why curators are so important. Unlimited access and a system of finding art that is based on hard data rather than flawed, thoughtful humans often favors a quick buck or hit of dopamine rather than what in the long run we know we really want— something that is fulfilling and rewarding. These systems are also often interlocking and self-reinforcing. You eat what’s available, you get a taste for junk food, and then it’s harder to break the habit of buying and consuming junk food without a concerted effort on many levels. Even inside the New York publishing business where theoretically people who work in the arts should have much more artsy taste than the average consumer, publishing professionals are trading in their copies of War and Peace for a 2000-page Romantasy series and young people working at movie studios are firing up Love Island instead of Casablanca.

Living in a society with more artistic taste is a non-linear and messy pursuit. Tastes change for any number of reasons, some that have nothing to do with the art itself. The last decade of escapism personified by Romantasy and reality tv is precipitated by dark times (pandemics, wars, elections). But one thing you always want in good times or bad to change the tides of taste is…

You Want Critics

Sundberg even kind of says this herself: “Just because you eat doesn’t make you a restaurant critic.” Her quote contains a false equivalency, though: a critic, is not a gatekeeper. Criticism serves a vital role to shake the system up. For everyone along the supply chain: gatekeepers, curators, and most importantly consumers.

What’s so enjoyable about Substack as a platform is access to long-form criticism that’s increasingly unavailable in mainstream publications. Personally, I’ve really enjoyed the music criticism of this Substack-discovered music writer antiart recently. Finding new music is a struggle once you’re past your twenties, so it’s great to have someone who keeps you informed, is looking for the cutting-edge, and keeps you up-to-date about the more popular sphere of music too. I enjoyed his review of Ethel Cain’s new album, an artist I knew nothing about previously.

Although one of antiart’s more recent posts “I Don’t Understand Taylor Swift Fans” underscores the tension between discourse and criticism that we’re all battling against in the 21st century. As I’ve stated before “hate the fans” is not substantive criticism. Antiart’s take on Taylor Swift ultimately echoes Emily Sundberg’s call for gatekeepers. The wish at some level that consumers just wouldn’t have access to or care so much about what is currently popular.

The way to convince consumers to have taste, to change what is popular, is not through calling them out, but in thoughtful criticism. Critics, not gatekeepers, give us the language and ideas to act on what we already know intuitively, what we already feel about the art from experiencing it. You will rarely ever sway a true believer, but there were plenty of fans who thought Taylor Swift’s last album was too long. A function of a good critic is, to some extent, to tell people what they already see, to share in it and unpack the particulars so that they have more nuanced ways of talking about it and telling others what they think. That is the essence of taste.

In contrast to antiart’s anti-Swiftie take, this piece from @cinephileandthecity “Miss Americana & The Paper-thin Album” is criticism from someone who is clearly a Swift fan but has taken the time to go song by song and say what she thinks does and doesn’t work (subtitle: “hey kids, criticism is fun!”— nailed it). It’s possible this writer will get someone at the same level of fandom as her to recognize flaws they already felt, reconsider what they think, and perhaps go look for art elsewhere to fill the void. In the end it’s curators, consumers with better taste, and critics—not gatekeepers—offer us the keys out of our predicament.

"...we’d like a system of filtering art that is less engagement-based and more human and thoughtful." Feel this in my bones. Yes to long-form, slow media and tangible experiences. We need less predictability and a bit more weirdness/humor and some gentle, intellectual rigor. Assume the audience is smart and sharp, and they'll show up for it. Thank you for sharing

I just wrote about Notes and how it scatters thoughtfulness as well!: https://open.substack.com/pub/hjzhou/p/an-analysis-of-substack-notes?r=1lpsdl&utm_medium=ios

I heavily agree with the point on curators. Many people forget that algorithmic feeds ARE a type of curator—a curator that’s less human and more interested in a complex set of engagement metrics. If one doesn’t actively seek out a thoughtful human curator with taste, in today’s digital world that simply results in giving up choice to the feed. That’s not good for a majority of people.

And yes, submitting to human curators sometimes means less-than-optimal programs. The Main Library at the San Francisco Public Library has a Lucky Day shelf, in which commonly checked out books are available for the day (no holds and no renewals). This is how I got to read Fourth Wing–which in retrospect may have been a Very Unlucky Day–but part of the fun is accepting you’ll simply hit out from time to time.