When I entered publishing, I had sort of an old school notion around youth, creativity, and commerce. Young writers, I thought, like young actors, musicians, and fine artists, were the prioritized commodity among both the professional apparatus that sell the art and the people who consume it. This has been a good rule of thumb since Mozart was performing at age 5. But growing up in the early 2000s it was an equally easy conclusion to draw. My generation saw the meteoritic rise of Britney Spears and *NSYNC, of Hilary Duff and Lindsay Lohan, of Leonardo di Caprio and Josh Hartnett. For a time, it seemed like all of culture would forever favor the hotter and the younger. A quick start seemed paramount to success and money and attention always seemed to gather around new stars.

My impression was that writing was no different, that of the apparatus’ attention and resources would be given disproportionately to promising younger writers. From Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis in the 80s, to David Foster Wallace and Donna Tartt in the 90s, to Zadie Smith and Jonathan Safran Foer in the early 2000s. Young genius is a publishing strategy that I believed still existed. My feeling was that older writers were therefore at an unfair disadvantage, that lists about debuts and writers under 35 were ageist.

Then my perception of the media reality I grew up with began to be supplanted by the reality of working directly in a creative field. I watched as none of the young writers seemed to gain traction, and as in other creative professions the young, exciting artists never seemed to really gain or maintain a foothold for big, culturally and commercially important careers (sans more recently Taylor Swift, the exceptions of all exceptions). Whether it is Millennial or Gen Z artists, the stars, the huge successes, just aren’t there. Meanwhile the oldest Millennials, Gen X, and the ever-present Boomers seem to be thriving.

Publishing mirrors the rest of society, where older people remain in power in politics, in business, and even at the box office. Obama, viewed as a young president when he first took office, is in fact a Boomer, born in 1961, a year no sitting president has been born after (born in 1964 Kamala Harris would be the first Boomer/Gen X cusp president). Out of all of the Fortune 500 companies only 40 CEOs are below the age of 50. Of the top-20 actors who are the biggest box office draws, only 4 of the actors are in their 40s (including Bradley Cooper, 49), one is in their 30s (Scarlett Johansson, 39), and one is in their 20s (Tom Holland).

In publishing, older authors dominate literature and even grow stronger later in their careers. A few weeks ago we talked about Percival Everett who, 23 novels into his career, finally struck it big. I also think of writers that are prolific, critically adored, and commercially successful in the last decade like Ann Patchett, Barbra Kingsolver, Richard Powers, and Colson Whitehead. This is not to pit the generations against each other. Unlike other realms of art and commence, publishing has never felt like a zero-sum game. These older authors are all writing consistently great books and occasionally transcendent ones. But book publishing is unlike business or politics where there are a finite number of positions to be occupied and unlike movies where there are limited budgets constraining who gets to make what. Older writers can’t hold younger ones back from writing great books even if they wanted to. So why aren’t there younger writers filling these roles? Where are our millennial Zadie Smiths, Ann Patchetts, and Stephen Kings?

Why Aren’t Millennials Writing?

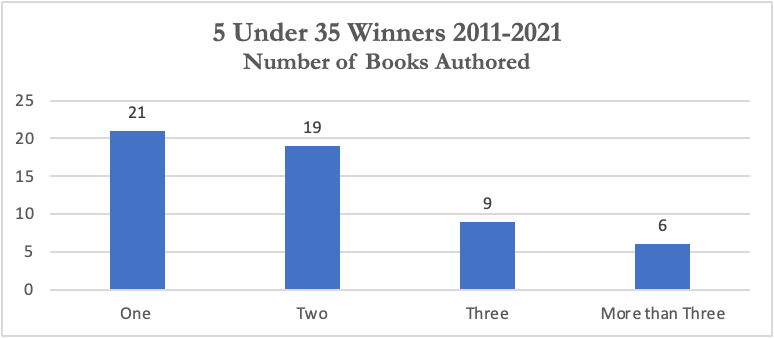

I did a little digging to see if my perception of there not being literary career titan writers under the age of 45 matched the actual reality. I started by looking back at 10 years of the National Book Foundation’s “5 Under 35” list, from 2011-2021, so that every writer had a least a few years to have a career and so that the hypothetically oldest person would still be under 50 today. The point of this dataset is to look at a list of writers who gained notoriety early on and see what happened with their careers, to see if, in fact, things have changed for the next generations.

Of’ the 55 novelists, nearly half (21) would never go on to publish another book after they won this distinguishing award for being a young and promising writer. An entire generation of talented literary writers are not producing or having writing careers in the way they used to.

Of the 34 writers on these lists that did go on to write more than one book, they averaged a book about once every 3.5 years. Why are authors in this generation writing so few books? One reason may come down to economics. A) There is not enough money in books, especially literary books (if there ever was) to support many writers making writing their full-time gig. B) As writing and publishing has become more democratized, open to writers that aren’t just at the very upper echelons of society (think Edith Warton, F. Scott Fitzgerald, etc.), more people get a chance to write and publish, but not necessarily make it their life’s vocations (see reason A). It also becomes the chicken or the egg, with there not being many career Millennial and Gen Z authors, publishers are not aggressively investing in the long-term career of younger literary writers, and then those writers justifiably feel like they can’t get enough investment to rationalize writing full time.

One of my favorite books of the past couple of years was The Regrets by Amy Bonnaffons. Aptly called “Murakami for the millennial generation,” The Regrets was praised to the hilt, sold modestly, and Bonnaffons — much to my chagrin — hasn’t been seen since. Meanwhile, the 75-year-old Murakami is publishing enough books that one is about his t-shirt collection.

And yet, putting economic factors aside, there is something strange going on. Let’s take the writers from the list who did have enough success right out of the gate and continued to write. Authors like Justin Torres whose books were selected for the Times’ Best Books of the 21st Century or Yaa Gyasi whose debut novel has sold almost one million copies—both of these authors have still only written two novels a piece (Gyasi two books in eight years, Torres two books in twelve).

Or, take a closer look at Brit Bennett’s career, which has pretty much gone as perfectly as it could in the modern era. She was awarded the 5 Under 35 designation in 2016 with her debut novel The Mothers, which sold well, was received well, and set her up to have a career. Then she wrote Vanishing Half, which published in 2020 and was a massive step up on all fronts—one of the best-selling books of the year, shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, and named a best book of the year by The New York Times. And yet, as of this writing that’s only two adult books in eight years, with no new book on the horizon. So, what has Brit Bennett been doing if not working exclusively on her next novel? The answer is working for American Girl dolls, to create a new character and write two accompanying books for young readers. This is worthwhile work, but it is exemplary of how economic opportunities whether in academia, Hollywood, or even with toy companies suck up the literary talent and attention of the younger generation. Who can blame them? Why do something that is harder (write a novel) and pays less money than do something that is easier and pays more?

Bennett’s example and many others on these 5 Under 35 lists suggest there is something larger afoot. Writers of a different generations, like musicians, and even movie stars, are finding it harder to maintain cultural and commercial relevance with staying power. And hand in hand with that is distraction on all sides. Audiences who are distracted and flinty with a million-and-one entertainment options and a reciprocal distraction from the artists themselves. We live in a time where actors are tequila moguls, rappers are actors, and seemingly everyone owns a makeup, clothing, or lifestyle “brand.” Creative careers are run as empires rather than as individuals who are maximizing creative output in the one discipline they are exceptional at. Writers are no different. Take even the most prolific writer in our sample set Akwaeke Emezi who has written an astonishing eight books in just six years. But in this time Akwaeke has also released a music album, written poetry, made films, and executed visual art projects. Even the popular artists who produce these days are multi-hyphenates pulled in a thousand splintering artistic and commercial directions.

Exceptions to the Rule

I’m interested in who will be the titans of literature for my generation, but the counterpoint is that commercial writers, primarily fueled by the boom in romance in all its forms are also doing quite fine when it comes to prolific efforts and millions of copies sold. Sarah J. Maas, Emily Henry, Colleen Hoover, seem to have no problem pumping out novels the way Danielle Steel, Lee Child, John Grisham did in earlier decades (and still are, as we see older people stick around longer and be successful in every field).

There are of course, exceptions that prove the rule in the literary sphere. Sally Rooney always comes to mind. Sure, I may have watched three Jeopardy! contestants not know who she was at some point, but she’s still about as popular as a literary novelist can be. Her fourth novel comes out this year and that will make it four in seven years, an outlier for writers in her age bracket. An irony given Rooney is often called the millennial novelist, but has an old-school career like very few, if any, other writers in her generation. Her persona and approach seem to be out of the ordinary in other ways—the screenplays she’s written are adapting her own novels, she’s not on social media, and love or hate her novels, she’s taken her success and seems focused on being a writer rather than anything else. That’s illustrative of what could be, and in twenty years the cultural tides could shift again and some of these writers will have written 12 masterpieces, but for now we must find our own distractions knowing that our next favorite author will take their sweet time.

I am an elder millennial writer (37), but I am just starting out in my career, currently in my first year of an MFA program. I think economic conditions have made it difficult for many writers of my generation to not only break into the publishing industry, but continue publishing, the way previous generations did. It's harder, much harder, to work just enough to pay the bills while giving you enough time to not only improve your craft and then write your first novel, but also figure out how to get it published and then market it. I tried that for my first 35 years before giving up and applying to MFA programs. Many writers my age sunk their formative years into building a career on the internet, either through blogs or personal essays for outlets like Buzzfeed, and that has worked out for some, but it was never a stable career and takes creative energy away from writing fiction. As does the route of building a platform on social media. Going the MFA route in your twenties does seem to result in a lot of debut novels, but as you noted, does not necessarily support the author in publishing the next successive novels that might grow their reputation. Successful debut novelists still have to hustle, and hustling takes time away from writing, and the hustle can become the primary creative outlet for many. I remember reading an essay from Emily Gould ages ago, where she talked about how she had to work odd jobs after her debut novel in her early twenties failed to sell well. She is still writing, but has become known more for her personal essays, in outlets like The Cut, than for fiction.

We just don't have the economic conditions to support many "literary giants" of any generation. And beyond the material conditions, the publishing industry spent like 15 years telling writers that they wouldn't be successful if they didn't become social media superstars. I am hopeful that this bit of conventional wisdom is dying out, because I suspect that Sally Rooney's lack of engagement with the internet has more to do with her prolific output than is often assumed.

We'd need to look at the 5 Under 30 list going back to the 70s to draw meaningful comparisons, but unfortunately that award was only established in 2006. For what it's worth, there are plenty of National Book Award winners from past decades whose names are unknown today, suggesting that those writers' careers were far from guaranteed as well. I also question whether this post overestimates the expected output of a prolific literary writer; is 3.5 years for a respectable book a long time? (Compared to what/who?)